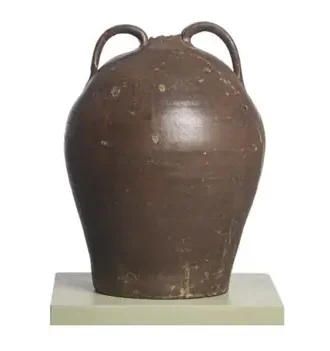

A jug tells the story of the African American Museum of Dallas. Harry Robinson, the founding director of the museum, always wanted to have a piece by David Drake. This artist was better known as Dave the Potter, who in 19th The black man was considered the first enslaved potter in the 17th century.

“We never thought we would get one,” says Robinson.

The museum celebrates its 50th anniversary.th anniversary in November, has proven time and again that any ephemera important to the history of black Americans could be purchased and displayed in the rooms of Fair Park, no matter how rare.

“Before I die and go to Jesus, I wanted a Dave the Potter,” Robinson says. When he found a collector who had one but wouldn’t sell it, “I wouldn’t let him leave my office until I had it.”

In fact, Robinson told this story while standing proudly next to 5 gallon jug in the Sam and Ruth Bussey Art Gallery, a space the size of a small apartment. It is enlivened by a mix of furniture, decor and folk art made by black people. To understand why Dave the Potter is so important to Robinson, consider this: The 19th-century potter was the first known enslaved potter and also a poet. He was also a rebel, both in his practice and in his personality. The South Carolinian labeled his pots and jars, which was rare because it was illegal.

While he made thousands of pots and jars over the course of his life, the National Gallery of Art estimates that only 270 remain. Robinson did not disclose how much the museum paid for this one. But one recently sold at auction in 2021 for $1.6 million. The buyer was the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, founded by Walmart heiress Alice Walton. Another is currently on display at the Dallas Museum of Art in the performative show When you see me: Visibility in contemporary art/history.

Each acquisition is special to Robinson, and he approaches it methodically, which makes sense for a librarian and archivist, a group of highly organized and diligent professional collectors. Next to Dave’s potter’s jar is a spoon by silversmith Peter Bentzson, which the Smithsonian says is one of only 10 known spoons and 20 pieces of silverware in existence. There’s also a folding bed by Sarah Goode, who in 1885 became the third black woman to receive a patent. (“People say she’s the first,” Robinson says. “She’s not.” The first two were Judy Reed and Miariam Benjamin.)

They are three of the 350 works of art and artefacts in the permanent collection and 60 archives that span the 18th century to the present day. But Dave the Potter is also a big deal because Robinson knew how important Dave the Potter was, and that meant the museum needed one of his works so everyone else could learn about Dave the Potter, too.

Robinson speaks confidently, seems to have an opinion on everything and knows how to tell a story. He has a stubborn streak and a charming ego.

Robinson has been the museum’s sole executive director since he founded the institution in 1974 in Dallas at the now-closed Bishop College, where he also directed the library. The museum has had several locations, both due to Bishop’s financial instability and a failed capital-raising campaign. After a successful second capital-raising campaign and money allocated after a bond election, the museum finally broke ground in 1989 and opened in 1993 in the cross-shaped building in Fair Park, off Grand Avenue.

In his eyes, he has created an unrivaled encyclopedic museum with a vast collection documenting black life through textiles, furniture and baskets that would make little sense for more traditional curators to store or display. “We don’t have any glass – not yet,” Robinson replies.

Random ephemera are the core of any regional museum. They are repositories of local archives, family heirlooms, and photographs. Names of prominent local black leaders are scattered throughout the museum. The Solarium is named after former MP Helen Giddings. They house the archives of the original Dallas Expresswhen it was still a black newspaper, and the Juanita Craft Civil Rights House Collection. But it also houses the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame and the archives of sepia Magazine that started in Fort Worth.

So while it has the same collection and character as any regional museum, Robinson wanted it to be the greatest museum of black history, a goal worthy of burgeoning Dallas. Granted, that goal was announced before the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in Washington, DC, in 2016. Robinson, of course, attended the opening, was impressed, and toured the White House, realizing that his museum’s collection complemented the larger one in the nation’s capital.

The museum’s first acquisitions in the 1970s were folk art works, which still make up the museum’s largest collections. The Billy R. Allen Folk Art Collection, named after a founding board member, now includes more than 500 objects.

Every ten years or so, black folk art is the subject of a major exhibition. Robinson rightly dislikes the term “self-taught.” It implies that someone was not skilled in anything. The artisans were trained basket weavers, silversmiths and potters, and through their work they told the story of black life.

“They paint based on their life experiences, no matter where they are,” he says, “and typically use religious symbols.”

One of them, Sister Gertrude Morgan, considered herself a religious figure. “She thought she was married to Jesus,” says Robinson.

In 1976, the museum inaugurated the annual Southwest Black Art Competition and Exhibition, later renamed the Carroll Harris Simms National Black Art Competition and Exhibition in honor of the co-founder of the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Texas Southern University in Houston. Local businesses donated money to finance the purchases.

He is not finished collecting yet. He mentioned the gaps in the collection. He would like to have sculptures by Bill Edmonson and paintings by Horace Pippin, among others. He would like to expand the design collection. He would like to curate more exhibitions.

Then he had to end the interview. He had to call a donor.