Cover imageTilly wears a cotton glove bodice from the Spring/Summer 2001 collection by MAISON MARTIN MARGIELAPhotography by Edward Mulvihill, styling by Rupert Carr-Gregg

After almost a decade Tilly Lawless is ready to turn her back on Instagram. The Australian author and sex worker, who has over 50,000 followers on the social media platform, first made a name for herself as a writer with her long, outrageous confessional captions about friendship, sex work, queer nightlife and romance. But like many other artists and writers struggling with the platform’s myriad pitfalls, Lawless retreated from the app during the pandemic, citing a number of factors: lack of privacy, online criticism, parasocial relationships and the fact that her Instagram account kept getting deleted without her consent.

Instead, she sought refuge in the novel, her debut book Nothing but my body was released in 2022, a visceral stream of consciousness that tells eight days in the life of the protagonist as she navigates through brothels in Sydney, drugs in Berghain and the horror of the 2019-20 Australian bushfires (her inspirations for the book were Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway). Nothing but my body was marketed as autofiction – that equally praised and despised literary term describing a mixture of autobiography and fiction, popularized by people like Chris KrausRachel Cusk and Sheila Heti – although Lawless now says she is strictly against genres and insists that these categories are invented by publishers to sell books. Despite the ever-changing literary trends, Lawless has always marched firmly to the beat of her own drum and has shown an absolute refusal to be pigeonholed by anyone (nowhere is this more evident than in her 2017 Ted-Talk – The best pages on the topicwhere she walks up and down the stage in a red, low-cut dress and black stilettos, rambling intellectually about sex work and feminism).

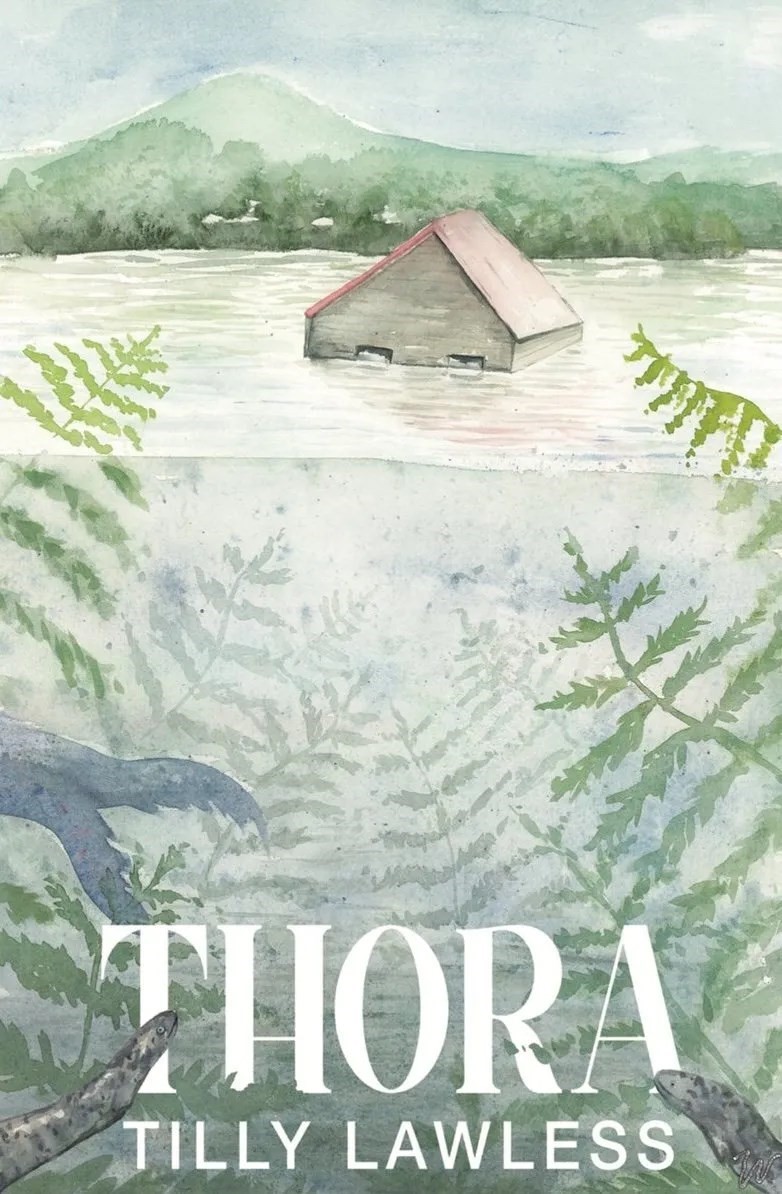

Lawless’ new book, Torahis further proof that the author will never do what is expected of her. A sensual young adult novel with hints of magical realism, the book centers on Rhiannon, a young girl in New South Wales (a uniquely green part of Australia) in 2009, struggling through high school, friendship, drugs, a lesbian awakening, and a troubled relationship with her mother. A nostalgic ode to Lawless’ own youth and hometown. Torah is characterized by the pursuit of pleasure, with the characters equally striving for sex and nature. When Lawless first pitched Torah When she approached Australian publishers, they tried to get her to censor sex and drugs in the book, but she refused. In the end, she decided to publish the book in all its graphic, sensual glory, with London-based publisher Worms. “I wanted it to be explicit, partly because I think the ‘young adult’ genre is too sterile for teenagers,” she says, pointing to shows like Heart Stopper.

Below, Tilly Lawless talks about her departure from Instagram, her struggle against whitewashed mainstream portrayals of teenage life, and her dislike of the term “autofiction.”

Violet Conroy: How did you start writing on Instagram?

Tilly Lawless: I wrote long, complicated stories all my childhood and adolescence, from the age of seven. I tried to write my first novel when I was 15, and I started writing on Instagram when I was 22. One day I wrote a caption explaining how a photo was taken and a friend said she really liked it. This was before anyone wrote long captions on Instagram; back then people only did Valencia filters and food photos. That’s when I started using it as the equivalent of a blog or diary, which is funny now when you think about it, because in the ten years since then things have shifted to people mainly writing long texts.

VC: Has writing on the Internet influenced your own writing stylistically?

TL: It actually improved my skills as an editor because the word limit was so small, like 400 words. I would write something in half an hour and then spend an hour editing. It’s probably similar to the training people get in journalism when they have to work within a very specific word limit. It definitely refined my writing, and that was really helpful for me.

“People confuse the number of followers with power. And sure, it gives you social capital, but I have no political influence. And I don’t make any money from Instagram” – Tilly Lawless

VC: You recently wrote a post about stepping back from writing on Instagram. Why is that?

TL: I was getting so much criticism online it was almost crazy. I didn’t want that kind of attention, so part of it is about protecting my privacy. Also, during the pandemic, I felt so saturated with screens and online life that I wanted physical things. My Instagram was deleted a few times – I managed to get it back – but I realized it wasn’t the right place for my craft and creativity because it can be deleted.

I want things to be in print because that’s the only sense of permanence you get when you write. Also, I got older and had a different relationship with myself and the world around me. Since 2020, I’ve slowly retreated from Instagram and now I hardly post anything. I don’t feel the need to anymore.

Some of my relationships also became quite parasocial. People would interact with me in ways that were so inappropriate or bizarre, and I didn’t want that in the future.

VC: In what way?

TL: Women would come on to me in completely inappropriate ways, or when I was at a club, obviously on drugs and having a good time, people on the dance floor would tell me about the time they were raped. I understand that it’s because they feel like they know me and I’ve opened up online, so they want to open up in return, but they don’t think about whether that’s what I want to hear in that moment.

VC: So there is almost a danger in writing a confession?

TL: Yes. People were using me as an outlet for their own anger about things. I had become a representative of something to them – a symbol – and because of my number of followers, they no longer saw me as an individual. People confuse the number of followers with power. And sure, it gives you social capital, but I have no political influence. And I don’t make any money from Instagram.

VC: With Torahit feels like you have moved away from the autofiction of your previous book, Nothing but my body.

TL: Well, both have just as much of me in them, it’s just that the genres are different. I didn’t choose (the term) autofiction for Nothing but my body either, that was something the publishers chose for me. I think the debate between fiction and nonfiction is so silly because even in nonfiction, things are changed to make the narrative work better. And in fiction, it all depends on who you are. It’s such a melting pot; you can’t untangle it. That’s why I think it becomes reductionist.

VC: Torah is very sensual in terms of both the nature and the sex scenes. Both are about the pursuit of pleasure. Do you see a connection between the two?

TL: Ultimately, humans are animals. I think our connection to nature also has to do with those tactile parts of us and those urges that we can’t really understand. No matter what we do to control them, they still overwhelm us. Sex, like hunger, is one of those basic instincts. I like to indulge a little in those physical aspects of us. It’s about that something deep within us that makes us alive, and I think that same energy flows through nature too.

VC: You’ve talked about your problems with Australian publishers trying to censor this book to sell it to the young adult market. Tell me more about that?

TL: It’s just for young adults because publishers define anything that has to do with teenagers as young adults. Young adults are just a category to sell stuff. When books were first written, genres didn’t even exist. When Samuel Richardson invented the novel in the 18th century, people didn’t think about genres. Over time, we’ve decided to categorize them, but that’s mostly to sell things.

The publishers wanted me to censor the sex and drugs because they weren’t appropriate for teenagers, but I didn’t want to do that, so I published it with (indie publisher) Worms. There’s nothing in the book, sexual or drug-related, that I wouldn’t have done as a teenager. I also think it’s a class issue. The publishing industry is generally dominated by upper-middle-class women because you can’t make much money in it, and they thought these girls’ lives were dysfunctional, whereas for me it was just the life of a normal teenager.

“When the novel was invented in the 18th century with Samuel Richardson, people didn’t think about genres. Over time we decided to categorize them, but that’s mostly to sell things” – Tilly Lawless

VC: So you decided to go the niche publishing route rather than adapting it for the mainstream.

TL: Yes. I wanted it to be explicit, partly because I think the young adult genre is too sterile for teenagers. As a teenager, I either read adult books or read fanfiction online. And the reason you read fanfiction is because young adult stuff is so sweet. It’s like that TV show Heart Stopper – it’s sickeningly cute. What kind of teenagers live like that?! I’m sure there are some, but that’s not my teenage years.

VC: So in your opinion, most depictions of teenage life in popular culture are too sugar-coated?

TLS: 100 percent. I think a good representation of teenage life – or something I could identify with – was How to have sex. For some reason, people allow that darkness a little more in film than in books, because it’s still so divided into genres. In music now, there’s a reaction against genre division. Someone like Billie Eilish is cross-genre. And I think in films, too, that movement is allowed more. But if you go to a bookstore today, everything is still so traditional, and that comes from the publishers.

VC: What are you working on next? And how are you currently balancing sex work and writing?

TL: I don’t work in the brothel anymore, I’m just a private escort now. I have more time, so I write more, but I also get more writing assignments, like my Outlook Split. Next I want to work on a series of short stories in the style of dark, gothic fairy tales. The Bloody Chamber things like that, but it all takes place in a brothel.

Torah by Tilly Lawless is published by Worms and is available now.