The Xbox 360 era was one of the most exciting times in gaming. With the launch of Microsoft’s second home console came the Xbox Live Marketplace and, more importantly, the Xbox Live Arcade. This platform allowed developers large and small to get creative by being able to design and digitally distribute games that publishers wouldn’t normally consider worthy of a physical release.

Last month, however, Microsoft unceremoniously slammed the door to the Xbox 360 Marketplace, and dozens of games were lost forever. It’s estimated that between 47 and 220 games will no longer be available anywhere because they only existed on Microsoft’s 360 storefront.

This closure has once again highlighted the need for better game preservation options. Players can no longer purchase Diabolical Pitch, developed by legendary developer Suda51. Licensed games from South Park and Happy Tree Friends have disappeared. And many developers’ first forays into the gaming world have completely vanished into nothingness. It’s a sad state of affairs.

Following the shutdown, we spoke to several developers who lost their games in the shutdown to reminisce about Xbox Live Arcade and discuss the need for better preservation.

A time to remember fondly

For developers, Xbox Live Arcade was a place to express their creativity, where budding creators could hone their skills and release games that might otherwise never have seen the light of day.

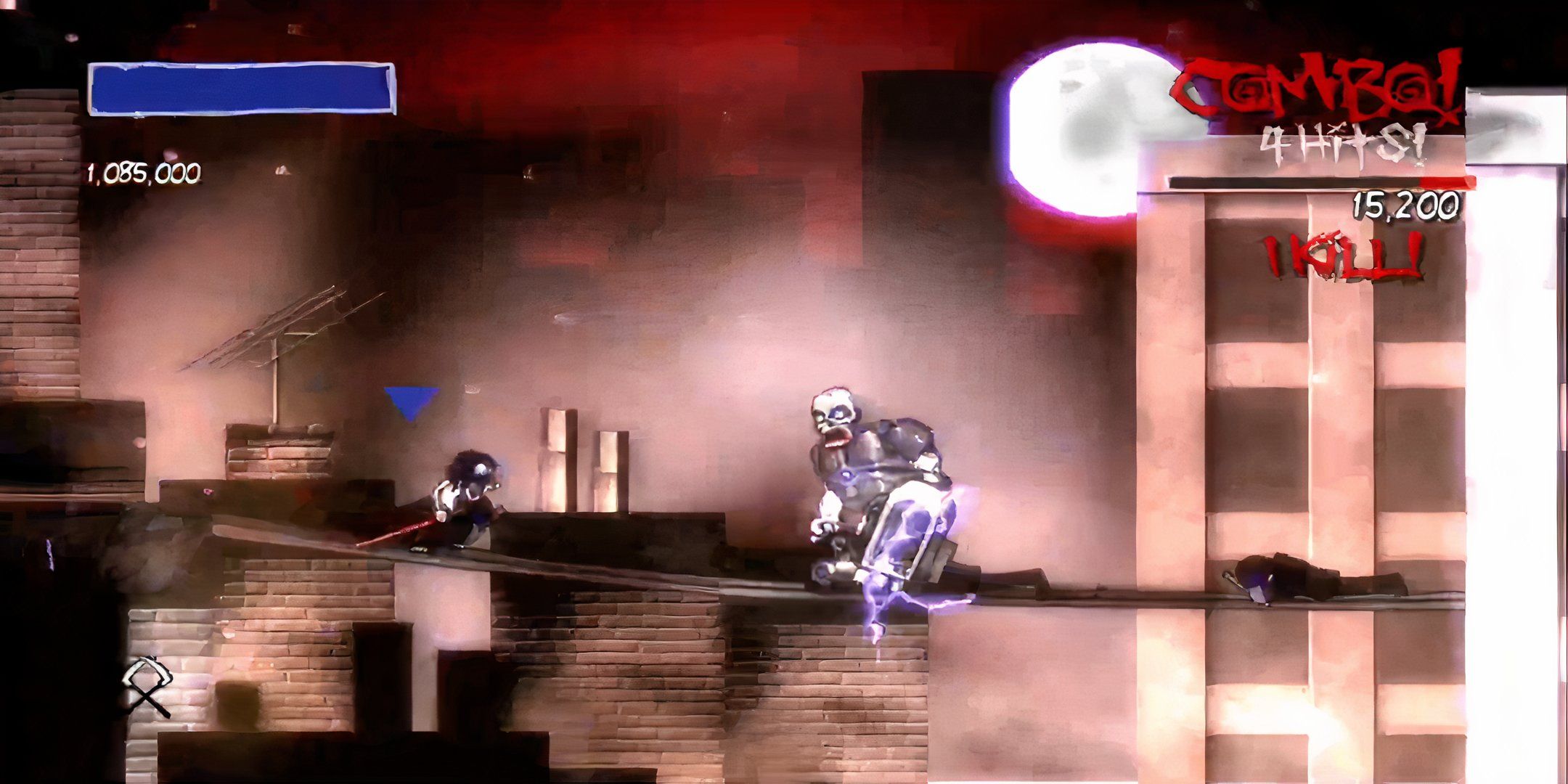

Ska Studio founder James Silva remembers what it was like to find success on Xbox Live Arcade. After several of Silva’s games failed financially, the indie studio released The Dishwasher: Dead Samurai, a stylish beat-’em-up that found an audience on the platform.

“To say I remember it fondly would be an understatement,” Silva says. “Since I was ten years old, it was my dream to have a career as a game developer, and for a decade and a half I spent almost all of my free time making games. It looked like a hobby, but it was the pursuit of a dream. And when Dead Samurai came out, it was like all those years of obsession had finally paid off.”

And it paid off. The success of The Dishwasher: Dead Samurai allowed Silva to pursue his dream, and after years of hard work, Ska Studios released the critically acclaimed Salt and Sanctuary in 2016, a dark mashup of the Metroidvania and Soulslike genres. With its success, the studio established itself as a mainstay of the indie scene.

It looked like a hobby, but it was the pursuit of a dream.

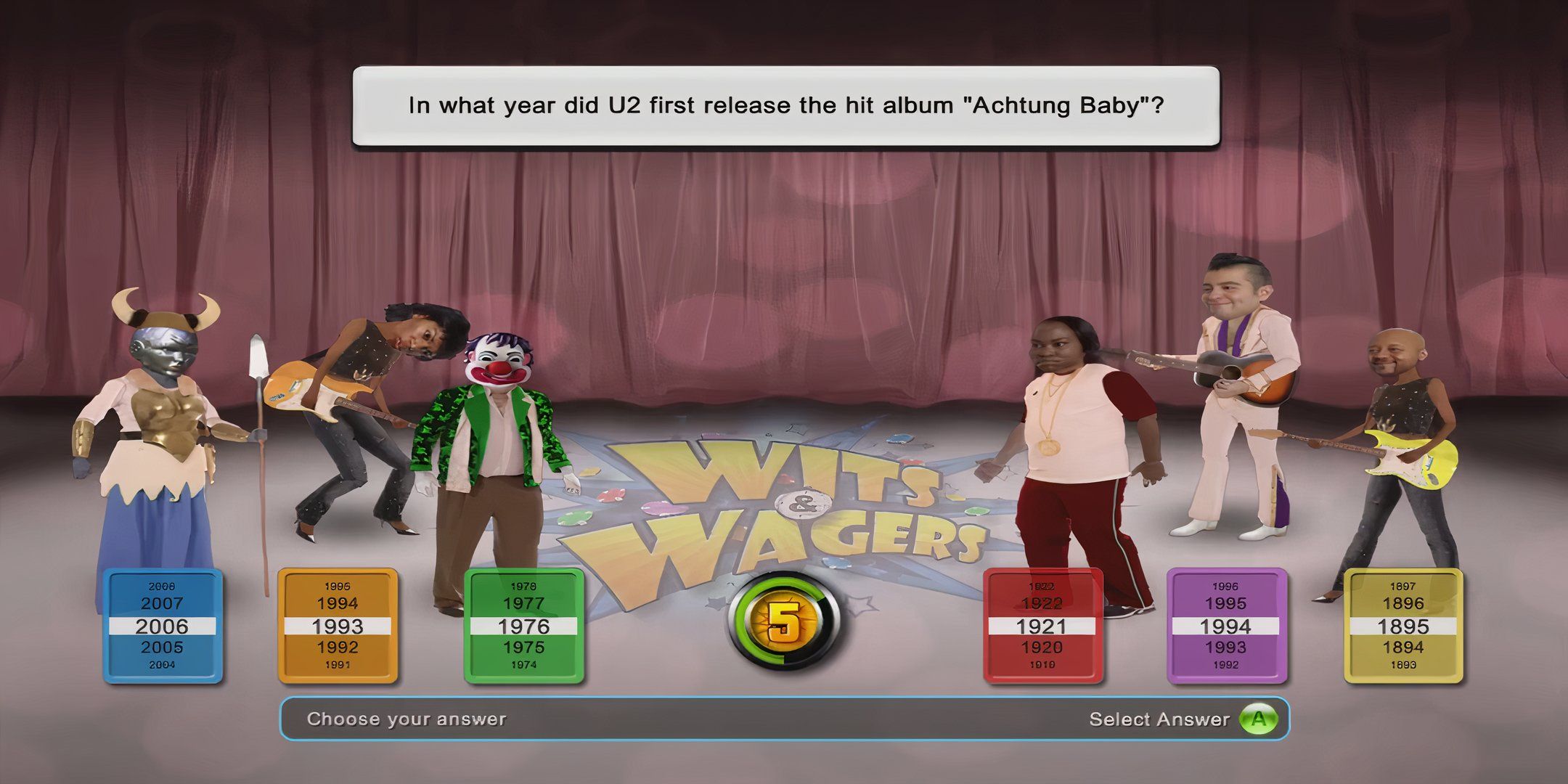

Jeff Pobst, CEO of Hidden Path Entertainment, had a slightly different experience than Silva, but one he remembers just as fondly. Microsoft approached Pobst during the early stages of Xbox Live Arcade to see if he and his team would be willing to develop video games based on popular board games, something he thought “Xbox would take a big initiative on.”

Pobst remembers the time he developed games for the platform, particularly Wits & Wagers, which you can’t buy anywhere anymore. “Wits & Wagers was part of the early days of Xbox Live Arcade, when they were still thinking about what games should fit on it. It was a video game based on a popular board game that could be played as a cooperative family game in front of the TV,” Pobst says. Unfortunately, the initiative to turn board games into video games never came to fruition, meaning Wits & Wagers was “a bit of an odd game in the Xbox Live ecosystem.”

Although the game seemed a bit out of place, Pobst says, “It was still fun and people said they really enjoyed it.”

A relic of time

Both Silva and Pobst told me that the possibility that their game might be unavailable at some point in the future never occurred to them. But that doesn’t make it any less annoying.

“It feels weird. Dead Samurai launched my career and now you can’t buy it anymore. That’s not OK,” Silva told me. But the store’s closure has given him the impetus to finally work on porting Dead Samurai to PC, something he’s been meaning to do for years. As we spoke, he even created a Steam App ID for the game.

“I don’t think any of us who made games in the ’90s thought that the games from back then could last 30 years or more – computers and consoles were constantly changing and the concept of backwards compatibility didn’t catch on until later,” Pobst tells me. He thinks that while it’s a shame the game is no longer available for purchase, it’s not that different from before. Those who owned physical titles could still play their games, just as those who bought a game digitally and downloaded it could still play it. “We could boot up the old consoles and play them (old physical games) – and I assume that’s still possible with Wits & Wagers today, it runs on my Xbox 360,” Pobst says.

It feels weird. Dead Samurai launched my career and now you can’t buy it anymore. That’s not OK.

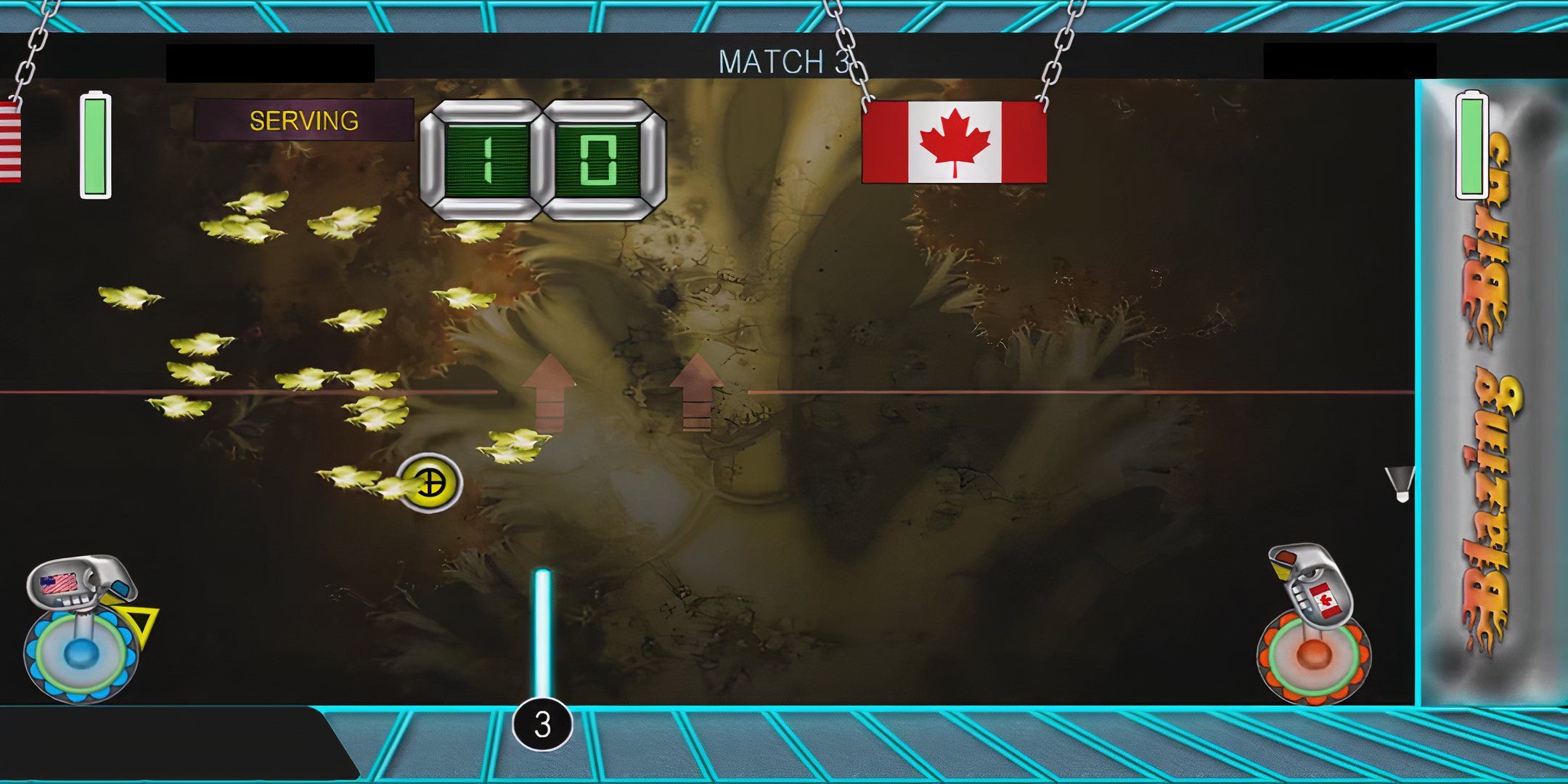

In addition to Silva and Pobst, I spoke with Jon Flook of Silver Dollar Games, whose recent releases include One Finger Death Punch. He told me that while it was “unfortunate” that the studio’s Blazing Birds game had been forgotten, he didn’t have time to look into it as he was “far too busy looking to the future.” The experience left a lasting impression on the studio, however, and Flook told me, “Since then, I would never consider making a platform-specific game again.”

Flook’s experience is very similar to that of Mark Edmonds, another developer I spoke to who helped develop the Microsoft-funded Fusion Genesis. Edmonds said, “It’s a shame it won’t be available anymore – it would have been great if it had been made backwards compatible for the newer consoles.” Microsoft’s funding and the game’s multiplayer elements mean that “it’s up to Microsoft” what happens with the game, and that “reproducing the server matchmaking functionality could be an issue.”

The need for conservation

Concerns about the value of game preservation have been around for years, with major companies quickly removing their games from stores or shutting down online servers in an emergency. This means there are countless games that are simply no longer accessible, at least not legally.

Interestingly, although this discussion crops up regularly on the internet, Edmonds tells me that in his 30-odd years as a game developer, 14 of them at Rare, he has never heard the content preservation debate discussed “much or at all” during the development of a game.

Although it is not discussed much within the development teams, Silva believes, “It would have been nice if Microsoft could support my Xbox 360 games through backwards compatibility, but that didn’t happen.” He speculates that the reason Microsoft did not make many XBLA games backwards compatible is because of the way they were developed. “If you look at the list of games built using the XNA framework, you will see that none of them have backwards compatibility support. There was probably a technical problem and the library of XNA games on XBLA was so small that it did not justify the effort required.”

Flook has a similar theory. “Preservation is difficult because the tools used to build them are often tied to other companies. I just can’t imagine those companies spending money on preservation,” he says. And Edmund is the third developer to express a similar opinion. He says that console makers and game developers need to standardize things so that “the standard platform code libraries that all developers use can easily migrate to future platforms, and the same goes for backend servers.”

Preservation is difficult because the tools used to create them are often tied to other companies. I just can’t imagine those companies spending money on preservation.

In terms of future preservation, Silva says, “The best thing developers can do is just release the source code,” although that comes with its own drawbacks. Releasing the source code “feels a bit like opening your bedroom closet to the world,” Silva tells me. However, he says he would “rather have people break into that metaphorical closet,” as he’s seen “a lot of people decompile my work to tinker with it, and I’m really grateful that’s happening.”

Pobst, on the other hand, is entirely focused on “entertaining people by making games of all genres,” and not necessarily dwelling on the past. However, he cites places like the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, and people like Don Daglow, a game industry veteran, who are doing really important work in the area of preservation. These museums and foundations like the Video Game History Foundation are trying to archive and preserve as many video games as possible, whether physical or digital, along with important design documents, marketing booms, and other gaming-related materials.

It is important that such work continues to be supported, as video games, like any other form of media, are an art and should be treated as such.