Blackout or erasure poetry is an exciting form. By skillfully deleting selected parts of an existing work, artists can extract or “find” something new from the previous version, which is why blackout poetry is also classified as “found poetry.”

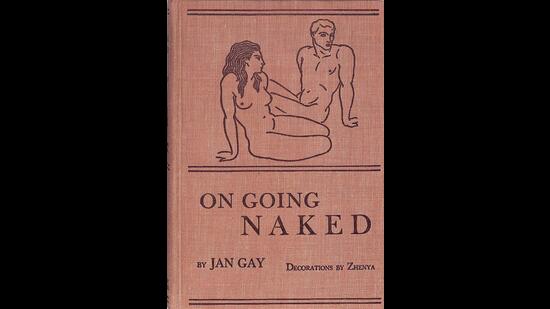

The concept of erasure is uniquely applicable to queer people, as LGBTQIA+ lives have been forever stripped of their history, making it difficult for them to imagine possibilities and futures. Examples abound. Attributed to George W. Henry, Gender Variation: A Study of Homosexual Patterns is a typical example. Henry, who “specialized in the study and treatment of homosexuality,” appropriated the research of German-born journalist Jan Gay, who was an openly queer woman.

Born Helen Reitman, she not only visited Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexology in Berlin, but may have also met the pioneering sex researcher. This visit—or interaction—was a pivotal moment in history, as it led Gay to conduct fundamental research to understand and document homosexual experiences. But what Gay found in the hundreds of interviews she conducted in the 1920s and 1930s was appropriated by Henry to associate queerness with deviance rather than socialize it as a variant of sexuality. At the time, women needed an expert, invariably a man, to certify their work and publish such research.

This singular act of erasure is at the heart of Blackouts, the genre-bending second novel by American writer Justin Torres. The novel is divided into six highly layered parts, enriched with queer stories and fascinating prose. It also includes photographs, forms of erasure literature, and extensive endnotes that elevate it to a kind of patchwork fiction. It won the 2023 National Book Award (USA) for Fiction and was a finalist for this year’s Orwell Prize for Political Fiction and the Lammy in the Gay Fiction category.

The book begins with the two main protagonists, Juan Gay and the unnamed character (who Juan calls Nene throughout), reuniting at the palace in a desert. The filthy and unattended place could be a metaphor for the abandoned, precarious state some queers find themselves in. The two have reunited after a decade, having first met at a psychiatric hospital where they were housed. Upon seeing Juan’s decomposing body, the narrator thinks, “There’s no way this body is my future.” Not only is he naive, but he also embodies the fantastical ignorance of queer youth. The transience and intensity of queer camaraderie and contact force him to fend for himself without any semblance of stability. Despite this, he is ironically convinced that his body will not let him down.

Back to the palace: Juan and Nene begin telling each other stories, a narrative device that becomes a tool for correcting historical omissions. It is also their way of using storytelling as a form of personal catharsis – a very clever meta-use. Example: “My parents fought about God. Physically. Then they passionately reconciled. They were teenagers. (You can imagine that, Juan. Nene, I can imagine that.)” Hidden in these sentences is Nene’s intergenerational trauma, his need to locate himself somewhere because he has (just like the author once did) “keys to nowhere”, and the awareness that his Puerto Rican identity marginalizes him even further (see “Puerto Rica Syndrome” in the book).

And then there’s Juan, offering Nene lost wisdom and making up for lost time. From mentioning the “lexicological shift” surrounding coming out to queer forebears—Zhenya Gay, Andy Warhol, Thomas Painter, and Edna Thomas, etc.—in the narrative to the discourse on eugenics, their dialogue allows the book to cover a whole range of topics. The most interesting and ambitious aspect of all, however, is the gaze. There’s a moment when Juan tells Nene how the “suddenly increased visibility” in the 1930s brought trouble for queers, and then lays out its relevance today:

“…If a police officer were to enter this room right now, where you are lying in this bed next to me in your skimpy underwear, so weak, he would see a crime.”

“What crime?”

“You are living together illegally; you sneaked in, didn’t you? And if a journalist came in, he would see a story, a scandal. And if a doctor came in, he would see a disease. And not just in my body, but in your head.”

Nene’s conversation with the dying Juan is also a form of care; a hidden aspect of this novel. The project he must complete in Juan’s name is a kind of inheritance – a rarity for queers. While Juan sleeps during the day, Nene immerses himself in “the books, the erasures,” and at night he begins to see Juan’s body come back to life, ready to delve deep into the past and relive it through storytelling. “Juan was dying, but only in the light and only in the body. In the dark, his voice filled the room, sharper and more alive than I was,” Torres writes. More than anything, this observation reveals the calculation of queer people’s lives. Because for most queers, night is the time of revival, of coming out. And any form of light signals recognition, a visibility that can kill them.

The novel also largely uses facts and documents as plot points. They are woven naturally into the narrative and make readers extremely curious about the thorny aspects of the fictional aspects. Moreover, Juan’s last name is not Gay for nothing. Torres writes: “He asked me to finish the project that had once occupied him so much, the story of a certain woman who shared the same last name as him. Miss Jan Gay.”

The award-winning author, who also teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), wanted to be deliberately playful with the book, tempting readers to wonder if Juan existed in real life and if the narrator is none other than the author himself. This blending of fact and fiction—the inherent queerness of Blackouts—adds to its charm even further. Try this statement: “Juan once said that when it comes to ghosts, you can either pretend they don’t exist, or you can listen.” Torres has done exactly the latter. By actively listening and telling this story, he undoes the appropriation, deliberate whitewashing, and erasure of the works of queer ancestors. Blackouts thus offers itself as a story masquerading as fiction. This is perfectly acceptable, as it doesn’t rob anyone of their future. Instead, it gives people power over their past and offers them control over their own narratives.

Saurabh Sharma is a Delhi-based writer and freelance journalist. You can find him on Instagram/X: @writerly_life.