The streets in Iowa City are too dark. You walk down Church Street and wish there were more lamp posts. Kirsten says she’s been trying to write a “Choose Your Own Adventure” story. As a kid, you loved flipping through the pages of a book out of order, so the challenge is appealing.

Article continues after ad

During the darkest months of Trump’s presidency, you wrote stories about Salvadoran children as a way to stay sane and counteract the scapegoating of migrants that reminds you of your own family members. Writing a CYOA story seems like fun, but will it help you preserve the dignity of the people and country that shaped you?

When you write the storyscroll down and read on.

If you do notscroll to the beginning of the article.

*

“In the West, fiction is inseparable from the project of the individual,” writes Matthew Salesses in his excellent book Crafts in the real worldAnd as scholar Glenda Carpio argues, this focus on individualism – or the assumption that immigrant writers “offer personal, semi-autobiographical accounts of successful or traumatic acculturation” – obscures the “larger historical, political, and economic conditions that lead to migration.”

Immigration is not an individual burden borne by migrants alone. You and I share responsibility, whether we know it or not.

In the pedagogy of creative writing, individualism is defined as “character competence”: Characters should be forced to make decisions. Interpersonal conflict moves a story forward. This advice does not apply to peripheral characters, however, whose scope for action is limited as soon as they appear on the scene. A story about an inmate cannot ignore the prison.

A migrant child poses a literary problem. A character without agency is not very convincing, but a character with too much agency seems unrealistic, especially when it obscures the social constraints to which it is subjected. This may sound like a pointless conflation of politics and literature, but they are one and the same. “Craftsmanship shows how one sees the world,” writes Salesses.

The question now is: how can we move from the individual to the structural in our narrative? In other words, how do you write the hero’s journey of someone who is rarely perceived as a hero?

*

Much of the debate around immigration focuses on the personal agency of migrants rather than the systems that govern their lives. Trumpian logic rests on their “choices”: parents chose to leave their homeland despite US warnings, and if their families are detained and separated, it is their fault. Violence is not cruelly inflicted, but is the deserved result.

To challenge these assumptions, I wrote a “Choose Your Own Adventure” story about a Salvadoran child who wakes up to find that one of his parents has left for the United States.

The story is written in the second person, partly because that is common in the genre, but also because it involves the reader and forces them to make the impossible decisions that Central American migrants face on a daily basis. (On the protagonist’s parents: “Who would you miss the most if you had to miss them again?”)

The protagonist is the migrant child, the reader and the author at the same time, a diversity that reflects the interconnectedness of our lives – and their struggles. Immigration is not an individual burden that migrants bear alone. You and I bear responsibility, whether we know it or not.

Then I could play with false choices. The story has dead ends that the reader doesn’t know about. The story ends or it returns to one of two points and only goes where I let it. To further this meta-commentary, I wrote choices that take away any real power from the protagonist and thus the readers. (For example: “The desert is your only choice. Turn to page 196.”)

Personal agency is only part of the equation. Even the most empathetic reader cannot guarantee the protagonist a happy ending.

The end result: a story that exposes the truth about immigration. Personal agency is only part of the equation. Even the most empathetic reader cannot guarantee the protagonist a happy ending. No matter how much they want it and how thoughtfully they choose, too many paths lead to starvation, death and misery.

*

In a rush of writerly power, I was tempted to fill my collection with happy endings—but that felt dishonest, especially when the news was full of images of children separated from their parents, of toddlers representing themselves in asylum court, of children losing what little control they had over their lives. If I could compel a reader to share even a drop of their frustration and pain, I was obligated to do so.

That should be our goal: to make the world and its systems visible in our fiction and then to populate it with three-dimensional characters. For me, that meant adopting my version of what Carpio calls “migrant aesthetics”: a set of formal strategies that “reject the empathy model of fictional relationships and invite readers to occupy positions, not people.“Life is about power differences – and fiction should be too.”

Central American migrants are not villains, animals, or monsters, but neither are they puppets with no control over their circumstances. They are fallible people navigating the system they were born into. Even if the gears are greased with their sweat, they have a say in their fate. If politicians and pundits don’t acknowledge this paradox, my fiction must.

*

A migrant child presents a literary problem. The solution lies in how one tells his story.

We write the world we want to see. The choice is ours.

__________________________________

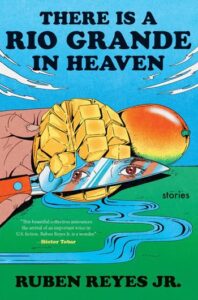

There is a Rio Grande in Heaven: Stories by Ruben Reyes Jr. is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.