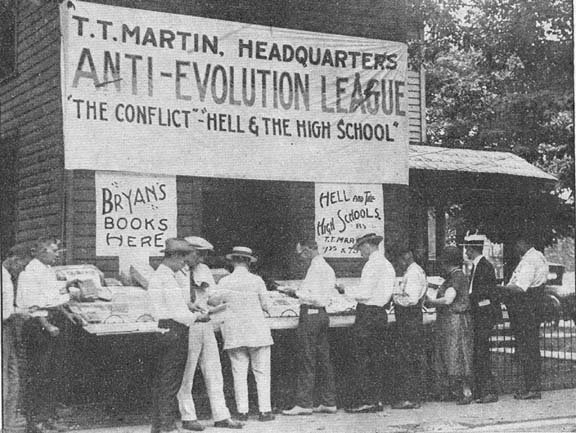

You may know the story of The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopesthe subject of Brenda Wineapple’s new book, Keeping the faithIn the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial,” as the trial is better known, the state of Tennessee prosecuted a high school teacher under the Butler Act, which criminalized the teaching of human evolution in the state’s public schools.

The trial, in which the well-known Christian populist politician William Jennings Bryan represented the state and star attorney Clarence Darrow represented Scopes, turned into a sensational clash between fundamentalism and modernism that generated eight days of media hype in the city of Dayton, Tennessee—and, as Wineapple’s subtitle shows, kept the nation on tenterhooks. Although the jury returned a guilty verdict, the court of public opinion overwhelmingly ruled in favor of Scopes, science, and academic freedom.

Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Divided a Nation

By Brenda Wineapple

Random House, 544 pages

Release date: August 13, 2024

Wineapple’s new book takes some time to get to the event it is about; before recounting the trial, the author devotes almost 200 pages to the most important developments in US politics and culture in the years leading up to the trial, told through the biographies of Bryan, Darrow and, to a lesser extent, others who later played a significant role in Dayton – such as Dudley Malone of the defense team and Baltimore Sun Reporter HL Mencken.

In these first, wide-ranging chapters (which cover the labor struggles of the late 19th century, the women’s suffrage movement, World War I, the first Red Scare, the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, the development of the fundamentalist movement, and much more), some readers may feel that the narrative strays too far from the topic.

But placing the trial and the spectacle surrounding it in such a broad context not only makes clear what brought Darrow, Bryan and other key players to Dayton, but also shows that the affair was the culmination of deep and long-building tensions. The account of the trial – the defense’s uphill battle against a biased court, heated exchanges between the legal teams and, of course, Darrow’s crucial decision to call Bryan to the witness stand as a Bible expert, thus putting him and his literal interpretation of the Bible in a corner – makes for a gripping courtroom drama.

Wineapple’s story also helps to clarify our public memory of the Scopes trial, which was not least influenced by Mencken’s cynical reporting for the Sunand the fictionalized portrayal of the story in the 1955 play He who sows the windwhich was later made into a film in 1960. We tend to neglect William Jennings Bryan, for example. As historian William B. Hesseltine writes in The Progressive On the 50th anniversary of the verdict, a two-dimensional caricature of Scopes’ prosecutor during the trial was “imbedded in the American consciousness.”

Keeping the faith treats Bryan as a serious and complex subject – showing, for example, that while his crusade against evolution was mainly driven by stubborn religious prejudice, it was also part of the populist beliefs that earned him the nicknames “The Great Citizen” and “Prince of Peace”. In the 1920s, Darwinism was eventually widely perverted to Laissez-faire Capitalism, imperialist conquest, and the eugenics movement (which both Bryan and Darrow detested) were viewed as examples of “survival of the fittest.”

Wineapple writes, “Bryan confused biological evolution with social Darwinism and therefore believed that the teacher Scopes advocated a ‘mutually devoured’ way of life in which the strong displace or kill the weak,” and he “confused the pseudo-science of eugenics with the theory of evolution.” He can be forgiven for this; even the textbook at the heart of the Scopes affair proposed measures to prevent “the possibility of the perpetuation of so inferior and degenerate a race.” Wineapple writes that it “combined eugenics and evolution with the social Darwinism that so deeply offended Bryan.”

The portrait of Bryan in Keeping the faith is fairer than the caricature we are used to. Yet he is also a complicated and deeply reactionary figure.

In addition to his religious fanaticism and his support of the right of the majority to suppress free speech – which is “not so different from the idea that might makes right” that he so despised, notes Wineapple –Keeping the faith repeatedly highlights Bryan’s white supremacy, which is even evident in his dislike of the theory of evolution, which he equates with naturalized violence and war. “How many more wars will it take before the white race wipes itself out… and leaves the world to the darker races to imitate the white races?” Bryan preached to a crowd in Dayton.

Although Darrow’s views on race and civil rights are easier for us to digest today than Bryan’s, Keeping the faith also presents Darrow as a complex man – a humanist champion of civil rights, free thought and the oppressed, but also as a human being: at times hypocritical, sloppy and opportunistic. Others to whom Wineapple pays less attention, such as Malone and Mencken, are also portrayed in nuanced ways.

In one of the few moments in Keeping the faith Wineapple specifically mentions the present, writing: “In Dayton, democracy was put to the test. Just as it would be again in our time.” She refers, among other things, to the fact that “teachers are told what and how to teach” and that “books are thrown out of schools and libraries.”

Readers with an eye on today’s culture wars in classrooms may recognize parallels between the anti-evolution sentiment that led to the Butler Act (and similar laws across the country) and efforts in recent years to eliminate lessons on race, gender, and other so-called “divisive concepts” from the public school curriculum.

Just as the moral panic over Darwinism encompassed various reactionary complaints about radicalism and atheism, the much-touted term “critical race theory” is similarly stretched by reactionaries today. The Scopes defense team’s objection that the Butler Act was too vague is also a reminder of how more recent “educational scam orders” use nebulous language to curb academic freedom generally. And their argument that the law “favors the fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible” is also a reminder of how some recent efforts to ban material from classrooms have been accompanied by attempts to introduce disturbing content that censors found more palatable.

In some ways, Bryan could be considered an intellectual forebear of today’s so-called parental rights movement. Many of his statements – for example, “Tell me today’s parents have no right to declare that this teaching cannot be passed on to children” – would fit well on this side of the modern educational culture wars. It is noteworthy, however, that while Bryan credibly claimed in Dayton that he was serving the will of the majority – as presumptuous and reactionary as that was – today’s parental rights activists, as Jamelle Bouie writes in her book Parental Rights, The New York Times“empower a conservative and reactionary minority of parents to dictate education and curricula to the rest of the community.”

And although Thomas Jefferson’s wall of separation between church and state is stronger today than it was in 1925, it has come under some serious attack in recent months, most notably in efforts to impose Christianity in the public schools of Louisiana and Oklahoma.

Beyond its impact on today’s curriculum battles, the Scopes trial remains deeply relevant 99 years later because it raised enduring questions about democracy and religion. As Wineapple writes, the Bryan-Darrow confrontation in Dayton “raised questions that have troubled America since its founding and continue to do so today.” Even nearly a century after this “trial of the century,” it is worth revisiting—with historical memory corrected and refreshed.