BRAINERD – A revenue stream that brought millions of dollars into county coffers and passed on to schools, towns and cities will dry up in 2025 – at least for a few years.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared Minnesota’s process for dealing with tax-delinquent property unconstitutional. The court ruled that Hennepin County violated the constitutional rights of Geraldine Tyler, a Minneapolis resident in her 90s, Minnesota Public Radio reported. Hennepin County sold Tyler’s condo for about $25,000 more than she owed in property taxes and fees and kept the difference. The Supreme Court ruled that she was entitled to the excess money. As a result, the Minnesota Legislature was under pressure this spring to quickly reform the state’s tax collection laws to avoid future lawsuits, MPR reported.

The state set aside $109 million to pay class-action lawsuits against the counties following the U.S. Supreme Court decision. The amount was determined after each county compiled lists of sold tax-forfeited properties. Crow Wing County, an active seller, had about 160 properties for which former owners or family members could seek compensation from the state.

Renee Richardson/Brainerd Dispatch

To fund the repairs, the state expects the county to make a “good faith effort” to sell tax-defaulted property at assessed market value by June 30, 2029, to replenish the $109 million. Counties must report their progress to the state annually and remit 75% of sales to the state through 2027 and then 85% of sales from 2028 to 2029. The percentage would serve as an incentive for counties. After 2029, the process would revert to the old model.

How does late payment on a property occur?

When a property owner stops paying the taxes on their property, they first go into default and are notified by mail and listed on a published notice of delinquent taxes. If nothing changes, the next step would be a court judgment against the properties in delinquency. Property owners have a three-year redemption period to remove the tax lien. If they do not, the tax-delinquent property belongs to the state, which is administered by the county. The county has received approvals or denials from cities, towns, or the DNR to sell property. Tax-delinquent property may incur costs to clean up. Finally, tax-delinquent properties are put up for sale.

In the past, the county offered these parcels at a public auction, and those that did not sell could be purchased over the counter. For example, if a property sold over the counter for $80,000, the county deposited $80,000 into the tax-foreclosed land fund. Money from the fund was divided with funds for county recreation, county capital projects, the county general fund, schools, towns and cities. For tax-foreclosed property, revenues typically exceeded expenses, resulting in more than $1 million annually for distribution between 2018 and 2022.

In 2024, revenues were $1,584,390 with expenses of $984,451, leaving $599,939 available. Of this allotment, $119,898 went to county recreation, $179,982 to county projects, and $119,988 to the county general fund, with $119,988 going to schools and $59,994 going to towns and cities.

Last year, the largest amount was distributed: $1,235,737 was distributed to county treasuries, schools, municipalities and cities in 2018. In 2025 and 2026, the allocation is expected to be zero.

Now the county will have three buckets, with all taxes forfeited before 2016 subject to the old rules. For properties forfeited between 2016 and 2023, different rules apply as the revenue is shared with the state. This affects about 170 properties across the county. And for all properties forfeited from 2024 onwards, a new forfeiture process will apply.

Stephanie Shook, assistant district attorney, said the 2016-2023 bucket is in response to the class action portion of the litigation and the agreed-upon lookback period. The district does not have to manage the surpluses for those properties because that will all be handled through the settlement.

“All we have to do is provide a list of all the properties repossessed during that period, whether a sale occurred or not, and they can file a claim immediately,” Shook said of former owners and interested parties.

“People whose property was forfeited during the look-back period of 2016 to 2023 don’t have to wait until the property is sold to make their claim,” said Deborah Erickson, county administrator. “They can make their claim through the settlement claim that Stephanie talked about. They can get their equity back. So we have a short period of time over the next four years to try to divest ourselves of these properties to pay back the settlement amount.”

As part of the settlement, a company was hired to notify those affected by tax forfeiture as part of the class action lawsuit. The county is not responsible for doing so, but must use its best efforts to sell the land at market value first.

Using the example of a property with an estimated market value of $80,000, for tax-forfeited properties dating from 2016 through 2023, if sold before June 30, 2027, 75% of the sale proceeds, or $60,000, would go to the state and 25%, or $20,000, would go to the county. If any of these forfeited properties are still in play after 2029, it would revert to the old process where the county could keep all of the proceeds.

Article / Crow Wing County

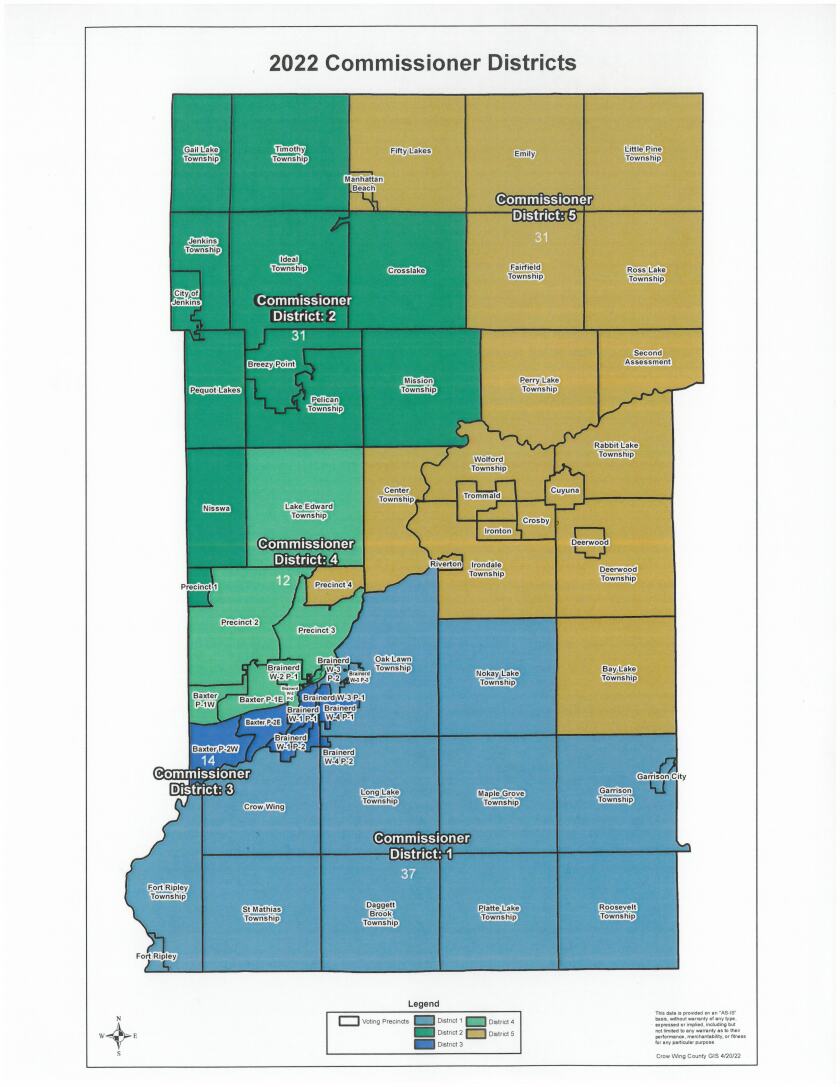

Tax-forfeited land by commissioner district with forfeited parcels from 2016-2023:

- 37 in District 1,

- 31 in District 2,

- 14 in District 3,

- 12 in District 4,

- 31 in District 5.

Under the new 2024 process, the DNR would be notified if a property is forfeited after the redemption period and could withdraw the property from sale. If that doesn’t happen, the county will send the previous owners a notice that the mineral rights were sold to the state for $50. There is a process in place for them to contest the value of the mineral rights. The property would then be put up for sale.

With an estimated market value of $120,000, the confiscated property would be sold at public auction for 30 days within six months of being confiscated. If the property is not sold within 30 days, it would be sold at public auction again with a minimum bid that covers all county costs, which in this scenario is $15,000.

If a bidder wins the auction for $80,000, the previous owners receive about $65,000 and $50 for the mineral rights. The county recovers its $15,000 cost of the tax-forfeited land fund. The county’s costs may include past taxes, fees, special assessments, interest, publications and staff time. The county notifies the previous owners of any surplus from the sale, pays them out, or initiates legal action to resolve rights to the surplus if, for example, there are multiple previous owners. The previous owners or an interested party such as their children have six months to file a claim. If there is any doubt about the legitimacy of the claim, the courts will decide the outcome.

On Aug. 20, Crow Wing County commissioners ran the numbers and learned the process will make tax-forfeited land more expensive to manage and dramatically reduce revenue from those sales. Additionally, selling tax-forfeited land to a local agency will no longer be as easy as selling land to a city for a park, schools or public housing. Staff will have to juggle multiple schedules and demands. All buybacks must be paid in full; there will be no options for contracts for land purchases, where in the past people put a percentage down and were financed. The panel was told cash is king.

Crow Wing County is using Public Surplus for the online auctions and more sales are expected throughout the year. A few counties are already using Public Surplus for the online auctions and more will likely follow, the board heard. Instead of holding an in-person auction once or twice a year, Erickson said there will be multiple online auctions, which will be more effective and increase the county’s reach.

Commissioner Steve Barrows said the state is making the county the real estate broker and seller. He asked if the county could charge a seller’s fee for that. Shook said there was a proposal for a 5% fee for the county, similar to a broker’s fee. Instead, lawmakers said the county could recoup its costs, such as publication and staff time.

“I suspect that this process is going to raise a lot of questions and a lot of things are going to happen, and I expect that in the next, I would even next session, we’re going to see changes, that there’s going to be adjustments here,” Shook said of the legislation that was quickly needed in response to the U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Reach Renee Richardson, editor in chief, at 218-855-5852 or [email protected]. Follow us on Twitter @DispatchBizBuzz.