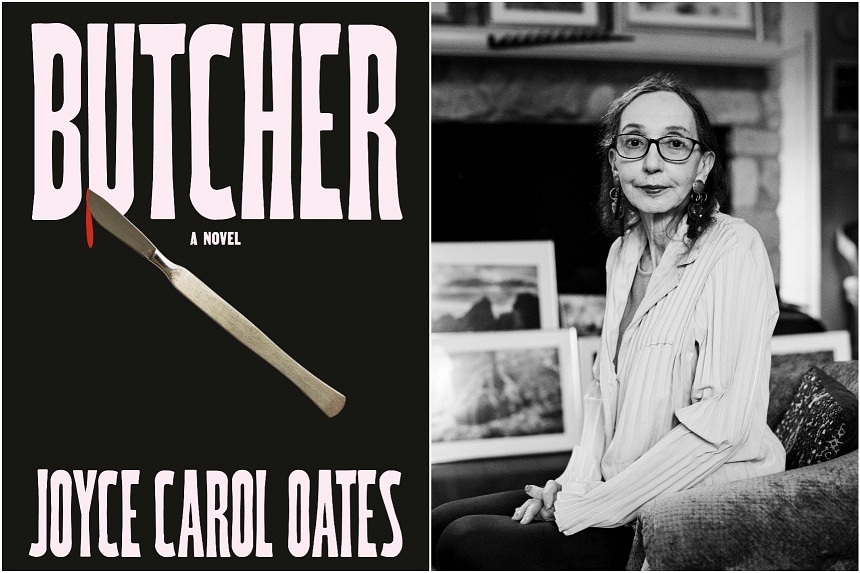

butcher

By Joyce Carol Oates

Fiction/Alfred A. Knopf/Paperback/332 pages/$32.16

The prolific Joyce Carol Oates once again takes a sadistic approach to the task, exploring the misogynistic and lawless frontiers of 19th-century medicine with a certain lack of inhibition.

As in her 2022 novel “Babysitter,” she once again subjects her female protagonist to a baptism of fire, refusing to mitigate the atrocities of patriarchy by skimping on blood and filth.

Here, however, there may be more erotic devotion than meaning at play, unlike, for example, the film auteur Michael Haneke, another artist who works in the same explicit manner.

“Butcher,” written largely from the perspective of the fictional father of gynopsychiatry, Dr. Silas Aloysius Weir, degenerates into one perverse operation after another, and its repetitiveness ultimately cannot be saved even by Oates’ sympathetic romantic language and tongue-in-cheek satire.

The beginning is promising. Readers first meet Weir as the awkward, still uneducated young doctor, not in the comfort of a clinic but in the home of a wealthy family, a brief, forbidding memoir narrated by Weir’s former lover.

His skin is unhealthily pale, “the hue of seriousness,” his suitor has failed, “the least attractive bachelor in Chestnut Hill this season.” The young man with the oversized forehead and spindly shoulders is the butt of jokes, overly serious, and bears a grudge for being less successful than his brothers.

A brief account by Weir’s skeptical mentor, a doctor, portrays him as a faint-hearted amateur with a psychotic streak who somehow manages to attain the powerful position of director of a state asylum for the female insane, tasked with developing a new method of curing mental illness.

What follows is the familiar story of a heartless man who must rule his own isolated kingdom, an incel with a god complex, free from the shackles of polite society.

In the name of science and providence, he begins to impose results by force and to dismiss deaths with twisted arguments. He completely dehumanizes his patients, removing their ovaries to cure them of mental illness or piercing their eardrums to numb their rebellious streak.

At the same time, he increases his reputation by announcing medical “breakthroughs” that are obviously false or happened by chance.

Oates succeeds in fully immersing herself in Weir’s worldview, and her deconstruction of the arbitrariness of 19th century medicine initially arouses curiosity.

Weir has difficulty recognizing the differences between patients and casually introduces sexist or classist views – “Hysteria is, in fact, a seizure that affects only women.”

He also cannot help but essentialize their beauty or ugliness and feel aroused by his dominion over their bodies. Oates cleverly draws parallels between the patients and indentured servants in the asylum and the black slaves in the American South.

Although this is an extreme case, Weir is not the only doctor to go astray. In fact, Oates tells readers that Weir’s story was compiled from the pen of several real 19th-century doctors, including J. Marion Sims, “the father of modern gynecology.”

In fact, Weir is taught earlier by his mentor that “a doctor is never guilty. Unfortunate people come to us for help, and we do the best we can, with God’s grace.”

He brings two women from the asylum to help him with his debauchery, but does not mention them in his medical records. Weir believes this is natural, as women are not in competition with him and must “naturally take their place as his subordinates and helpmates.”