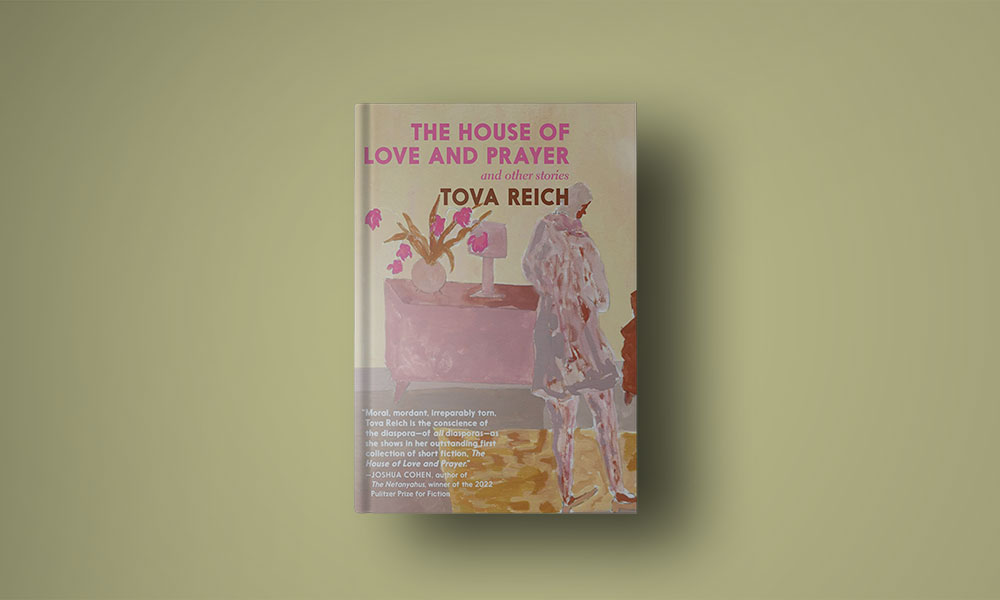

The House of Love and Prayer and Other Stories

By Tova Reich

Seven Stories Publishing,

256 pages, $26.95

AAmerican author Tova Reich has been writing fiction for a long time: Marathe first of her six published novels, appeared in 1978. The second, Master of the Return (1988) won the Edward Lewis Wallant Award, a prestigious Jewish literary prize, and the most recent Mother India (2018) was nominated as a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. Her books have earned Reich a reputation for profound knowledge of Jewish topics, including rituals, history, culture and texts, the experiences of Jewish women, various religious (particularly Orthodox) customs, the Holocaust and its aftermath, and Israel.

Her novels are also characterized by sharp narrative bite. Fifteen years ago My Holocaust– whose opening chapter in a modified form and under the title “The Third Generation” first appeared as a short story in The Atlantic and is included in the new book – was celebrated by some readers and sharply criticized by others. The story is about a father-son duo who run a morally questionable consulting firm called “Holocaust Connections, Inc.” and whose offspring, who represents the eponymous third generation, not only converts to Christianity but, as their second-generation father notes, becomes a nun in “that Carmelite monastery right next to Auschwitz, of all places.” What some saw as a brilliant satire on Holocaust education and remembrance, others found more than offensive. The issue became so heated that no less a figure than Cynthia Ozick publicly castigated both the then editor and a writer of the New York newspaper. Jewish Week for their denigration. (Ozick’s defense of the book can be found on the website of Reich’s literary agent.)

Reich’s typical themes and his distinctive style fill the pages of The House of Love and Prayer and Other Storieswhose publication marks the first time that her short stories have been compiled in book form. The volume contains stories dating back to 1995’s “The Lost Girl,” which was published in Harper’s and canonization in The Norton Anthology of Jewish-American Literature. Some of these stories are known to readers of literary magazines such as Conjunctions or Agni. Two parts, including the title story, appear to be published here for the first time.

Like Reich’s novels, these stories take place in settings both common and less common in Jewish-American literature, often but not always Orthodox settings. The sometimes unsympathetic characters often find themselves in extreme situations: in “The Lost Girl,” the principal of a girls’ school must deal with the disappearance of a student during a school field trip in the woods; the title story concerns Rabbi Yidel Glatt, who becomes so preoccupied with the sanctity of his body that he eventually dies of anorexia. Other stories are set in Israel, Poland, and China.

“Forbidden City” is a vivid example of her style. First published in 2004, the story introduces Reb Pesach Tikkun-Olam Salzman, a long-time resident of Beijing after being sent there with his wife, Rebbetzin Frumie, as an emissary from Brooklyn. But Reb Tikkun-Olam’s dubious activities, including a mutually beneficial collaboration with Chinese “bosses” involving the care and eventual adoption of the most vulnerable (often disabled) abandoned young Chinese girls in the United States, have led his distraught wife to leave him. Reich sums up the break in a typical style that is at once comical and terrifying, using one of her equally characteristic, exquisitely crafted long sentences:

But the last straw for Frumie was when he told her that while he would save all the other cast-out girls as part of his mission to save the world, to find them good Jewish homes and Jewish adoptive parents from America’s increasingly numerous elderly, over-educated, infertile, dual-income Jewish couples who could afford the fees, and thus, as a side effect of saving the children, also draw on the demographic abundance and genetic diversity of the Chinese to remedy the population shortage and chronic inbreeding among the Jews, and, as a bonus, add the additional service of personally converting the girls in advance by ritually immersing them in baths, like pre-kosher chickens, already salted and soaked—but this particular girl, this Dolly, his first, he would keep, not for his sake, God forbid, but for her sake, for Frumie’s sake, to raise Dolly so that she would serve as his Pilegesh when she came of age, so that he would no longer have to bother Frumie with his needs, even during the times when she was not ritually impure, although she was technically available to him, despite suffering from a terrible migraine.

If you click on pilgrimage for the first time (it means “concubine”), rest assured that you are not alone. Surely I am not the only one who appreciates the lessons (or refreshers) in Jewish literature that these stories can offer outside the adult education classroom. The details of the rituals surrounding death and burial, for example, are central to the third story, “The Plot” – in which two women in their eighties are brought together by a local Chevra Kadishaor bereavement committee – and reappear elsewhere in the volume. In “The House of Love and Prayer” one learns (or is reminded of) a number of details about circumcision.

Let’s stay here: Until I picked up this book, I was unaware that there was a real House of Love and Prayer corresponding to the fictional House of Love and Prayer that is in the title of the story (and the volume). It is in this fictional House of Love and Prayer in 1960s San Francisco that the story’s main character, the aforementioned charismatic Rabbi Yidel Glatt, meets the woman who becomes his wife (Tahara, née Terry, Birnbaum, “from a bagels-and-lox family from the Upper West Side of Manhattan”). But when I recognized a minor character—Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach—portrayed as the “guru” of the House of Love and Prayer, I paused. Google confirmed that there was indeed a House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco and that it was Carlebach’s domain. Particularly after the allegations against the real Carlebach have resurfaced in the #MeToo era, it seems important to clarify that these stories here, as elsewhere, contain material that some might find extremely disturbing. Some of the allegations against the real Carlebach actually date back to the 1960s, when in the story, before the arrival of her future husband, Reich’s Terry/Tahara spent nights “gathered with the other lost souls at Reb Shlomo’s feet, rising ever higher at his songs and streaming his stories, so that in those predawn hours, when the heart is clenched with fear, it was nothing less than an honor to be the girl called to his chamber…”

These stories deal with content that some may find extremely disturbing.

Every story in this volume is unforgettable, but perhaps the most striking—especially now—is “Dead Zone,” which closes the book. Here, Reich takes us into the future: When Isadore “Izzy” Gam dies in 2040, his great-grandson is only three years old. But as an adult, that great-grandson takes up Izzy’s extraordinary story and continues to tell it, largely because of its “peculiar” connection to something that happens not long after Izzy’s death. We learn this in the story’s very first line: “The United Nations’ decision to officially end Israel’s existence as a living entity, an event that occurred about a century after the vote to divide the Holy Land that led to the creation of the Jewish state in 1948.” (Need a minute before moving on? I needed it when I first read those words.)

The younger Gam explains: “The UN has so cleverly eliminated Israel as a state by simply declaring it a UNESCO World Heritage Site – as the largest Jewish cemetery in the world.” And this, he says, is actually connected to the atypical burial of his great-grandfather.

I’ve already pointed out that the theme of death is a common thread throughout the book. This final story raises the stakes exponentially, from individual death and the aftermath of the Holocaust to something so shocking that it may seem unimaginable. But when we acknowledge our Jewish past and consider the present, how unimaginable is that? What reaction does Reich want readers to have here, particularly in relation to the state – and the State – of Israel? As with each of the previous stories, the possibilities for interpretation are vast.

This much seems certain: If Reich’s novels have provoked strong reactions in the past, this collection will also inspire lively conversation. Try it in your book club – if you dare.

Erika Dreifus is the author of Birthright: Poems And Quiet Americans: Storieswhich was awarded the American Library Association/Sophie Brody Medal for Outstanding Achievement in Jewish Literature.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.