This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of writing Newsletter – register here.

Article continues after ad

The elevator at Brooklyn’s Center for Fiction is wallpapered floor to ceiling with novel pages and literary quotes. Authors like Toni Morrison and Philip Roth offer aspiring writers emotional support and inspiration as they make their way to their second-floor desks, hours of toil, and, hopefully, in due course, the publication of acclaimed books. I had always absentmindedly glanced at the wall writings while fumbling for my access card or silencing my phone, until one day a quote from AM Homes stood in sharp contrast.

If you don’t write the book you’re supposed to write, everything falls apart.

Like everyone else at the center, I was struggling to complete a novel, a dual narrative in which the stories of two women intersect in unexpected ways. An Albanian-born interpreter, with little regard for rules and boundaries, over-involves herself in the lives of the immigrants she works with, endangering her marriage and her sanity. A sheltered young American moves to New York City in search of excitement, encountering odd roommates and a problematic lover. The novel unfolds alternately between these two stories. There are striking parallels between the two women’s lives. Words spoken by strangers in the interpreter’s story become significant in the other storyline. Characters presumed dead in the earlier narrative turn up alive and well in the later narrative. Perhaps the stories were alternate versions of the same woman’s life, or perhaps one was a fictional universe a character had created. The possibilities were many, but the relationship between the two women was to remain elusive. The narrative would twist and turn around an invisible hinge.

Even now, looking back brightly and uselessly in retrospect, the idea sounds appealing. But I’d been trying to make the dual narrative work for nearly a year. I suspected that, despite all my revisions, I was still on a first draft. The story didn’t flow. The comments I received in a novel-writing workshop confirmed my fears. The narrative was choppy. The moment something exciting was about to happen, the other universe would intrude, presenting another dilemma or character that tested the reader’s willingness to open up. The writing style was uneven, stronger on some pages but less confident on others. Some said I’d described things too generally. Others that I’d gotten lost in details. The problem was that the two stories didn’t get along. My experimental structure was exciting as a concept, but completely lost its luster in practice, like a vacation in a tropical location with good friends, their spouses, and their children.

Even before the quote on the wall haunted me, I asked myself why I had chosen this double narrative. I liked linear stories, but I was also fascinated by experimentation. Was my inspiration Kieślowski The double life of Veroniqueasked a friend? I had seen this film so long ago that I wasn’t even sure I had seen it. Cortázar’s Heaven and Hell came to mind. It lived up to its title by allowing readers to jump through different versions of the novel, with the structure consistent with the chaos the characters experience. What did the dual structure reveal about my characters? I couldn’t yet say. The deliberate arrangement of the text drew the reader into a literary labyrinth, but the effort to achieve this distracted me from character development. If the “expandable” chapters at the end of Hopscotch revealed a deeper truth, my structure seemed to conceal it.

To find out if a novel is good, the novel must first sound good. Whenever I described my idea to others, the response was enthusiastic. An unusual structure, trying something new, gives you a certain prestige. But it was also true that novels by brilliant minds with cutting-edge structures didn’t captivate me when the characters were just vague descriptions and placeholders. I always thought Calvino had much more fun writing. When on a winter night a traveller than when reading.

I took my time before making a decision. Here is a quote that is not on this wall: When you wake up and want to google Mistake about sunk costs, Think seriously about your obligations.

BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS BY LEDIA ZHOGA

I decided to leave out one of the stories, but the scenes with the young woman who moves to New York made up half of my novel. I saved those pages in another file. I could put them back in at any time, I reassured myself, although I knew I wouldn’t. I turned my attention to the interpreter’s story and continued to develop the characters I had there, the interpreter’s relationship with her husband Billy and the immigrants she meets. At that point I only had about 30,000 words, but the dramatic seeds of what was to come were there. I had already written the scene where the interpreter and Leyla, a Kurdish poet she befriends, leave the KGB bar. On their way to the subway, Leyla fears that they are being followed and photographed by her husband’s cousin, which turns out to be false in this scene. But the potential threat was there, and it made sense to follow that thread and exploit it to illuminate the interpreter’s compulsion to help as a deeply rooted and sometimes dysfunctional character trait. To make sure I was on the right track, I put off writing the scene where she follows Leyla’s stalker Rakan to the shoe shop. But my instinct always seemed right – she had to get close to him. After I wrote the scene in the shoe shop where the interpreter gets Rakan’s phone number, the novel practically wrote itself. It only took me a couple of months to finish.

I decided to leave out one of the stories, but the scenes with the young woman who moves to New York made up half of my novel. I saved those pages in another file. I could put them back in at any time, I reassured myself, although I knew I wouldn’t. I turned my attention to the interpreter’s story and continued to develop the characters I had there, the interpreter’s relationship with her husband Billy and the immigrants she meets. At that point I only had about 30,000 words, but the dramatic seeds of what was to come were there. I had already written the scene where the interpreter and Leyla, a Kurdish poet she befriends, leave the KGB bar. On their way to the subway, Leyla fears that they are being followed and photographed by her husband’s cousin, which turns out to be false in this scene. But the potential threat was there, and it made sense to follow that thread and exploit it to illuminate the interpreter’s compulsion to help as a deeply rooted and sometimes dysfunctional character trait. To make sure I was on the right track, I put off writing the scene where she follows Leyla’s stalker Rakan to the shoe shop. But my instinct always seemed right – she had to get close to him. After I wrote the scene in the shoe shop where the interpreter gets Rakan’s phone number, the novel practically wrote itself. It only took me a couple of months to finish.

The story I had set aside had by no means disappeared. The two narratives had been crammed together for so long, corrupting each other as I intended. But I did not erase these reflections of the other narrative, as they added to the variety of the novel’s structure and color. The young woman in vintage outfits, the elderly artist playing live piano in Washington Square Park, the costume parties, the absinthe cocktails, the American and Indian versions of the Dirty Dancing films—all of these came from the other narrative. Like characters in an anamorphic projection, this other story is there, though visible only from a special vantage point. These brief gateways to a fantastical world complement the novel’s theme of duality and became part of the current plot.

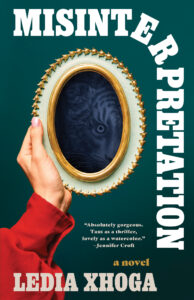

One of my professors in my master’s program was fond of saying that history is always smarter than the author. The pain of cutting one of the plot threads proved that to be true. But learning how to take a detour, the ability to make a difficult decision, and improvise are other necessary skills of a writer. The novel would not have been the same had it not taken the wrong turn. In Misinterpretation, fleeting glimpses of what was cut enhance the glimmer of the unknown, alluding to the ever-present possibilities that surround us as we immerse ourselves in new people and cultures. It is the transformation for which we all turn to fiction, an open challenge to our way of thinking and being.

_____________________________________________

Misinterpretation by Ledia Xhoga is now available from Tin House.