With the election of the Labour government, the will to solve the housing crisis in England has also increased. Among the first policy initiatives announced by Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner is the reintroduction of a national housing target: 1.5 million new homes during the five-year term.

This target applies only to England – the other nations of the UK have devolved powers over their housing stock – and includes privately built housing as well as “affordable housing”.

While the government’s desire to address this major housing challenge is commendable, achieving its ambitious goal requires two major challenges: first, identifying what type of new housing is needed and who will build it. And second, determining where it will be built.

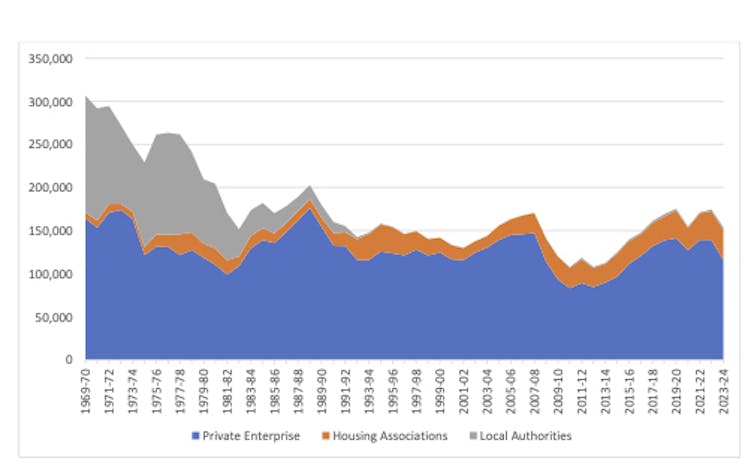

To oversee five consecutive years of over 300,000 homes being completed annually would be unprecedented in modern politics. The last time 300,000 new homes were completed per year was in 1969/70 under Labour’s Harold Wilson (see chart).

In 1978/79, the last full year before Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government came to power, local authorities across England built 93,300 new homes. By 1996/97, the last year of that Conservative government, this figure had fallen to 450.

During the same period, the number of new private homes built remained largely unchanged, ranging from 127,490 in 1978/79 to 121,170 in 1996/97. At no point in the intervening years did the level of private building activity compensate for the loss of social housing. Instead, around 1.3 million social homes were sold during this period under the Right to Buy initiative – effectively transferring the public housing stock into private hands.

And after 1997, none of the subsequent governments has managed to create anything like the average of 300,000 new homes per year that the new government deemed necessary.

Since 1969, new houses have been built in England every year

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2024

What kind of houses should be built?

Part of the challenge is defining what types of homes the government wants to provide. The scale of housing need in England is defined by a formula developed by the government, the ‘standard method’ for calculating housing need. Since its introduction in 2018, this formula has used a mix of population projections and an affordability ratio to determine the number of new homes needed in each English local authority.

However, the standard method does not distinguish between different types of housing: one-bedroom apartments for social rent, detached single-family homes for sale to owner-occupiers and everything in between are all counted as “housing”.

Policy in such an important area should be guided by a better understanding of the type and lifespan of the new homes we need, particularly in view of the changing housing needs of our ageing population.

The largest category of new housing lost is social housing – affordable rental housing. But if this Government is to deliver an average of Dh300,000 a year, it must incentivise the private development industry, housing associations and local authorities to all deliver a comprehensive housing programme that includes a mix of private and affordable new housing of various types.

None of the previous governments has been able to achieve this goal in recent times – also because they found the associated issue of location for new housing even more difficult to deal with.

Where should the new apartments go?

To understand the geographical distribution of demand for new housing, we need to return to the standard method.

The Government’s proposal – it is still a consultation proposal – makes some important changes to this formula. As well as placing greater emphasis on affordability, the most important change is a new base number of homes, calculated as a proportion of the existing housing stock in each local authority (instead of the population-based approach). The result is a national target of 371,000 dpa.

Under this new method, the need for new homes in Manchester – one of the UK’s most successful cities in terms of decades of urban regeneration – actually falls by 25% (from 3,579 to 2,686 dpa). In Greater London, too, the overall need for new homes falls, from just under 100,000 dpa under the old standard method to around 80,000 dpa.

In contrast, around 90% of English local authorities see increases under the proposed new method, some of which are very large. For example, whereas Cheshire West and Chester previously had a housing need of just 532 dpa, this increases to 2,017 dpa under the proposed new method.

If this seems strange to you, the explanation is that the existing housing stock has been made the most important factor in determining future demand. This may sound simple, but the logic behind it is questionable, to say the least.

The change to the proposed standard method also has a political dimension. Labour’s election victory means it has MPs in historically conservative ‘blue wall’ constituencies such as Aylesbury, Buckingham and Bletchley, Milton Keynes, Basingstoke and North East Herts – places where the contentious issue of delivering more housing on a large scale could pit electoral and local interests against party and national priorities in a way never before tried.

Real opportunities

Despite these challenges, it is extremely encouraging to see the Government starting its programme with a focus on housing. Importantly, this presents real opportunities to make progress on housing in England.

The creation of a New Towns Taskforce is a response that is both scaled and ambitious to the housing crisis. However, New Towns are, by their nature, large-scale developments where there is no existing community – the exact opposite of the core principle of the new standard approach.

In addition, there is clear potential in revitalising England’s declining shopping centres, which, although well connected, are suffering from increasing levels of online shopping by consumers.

Investments in new towns and shopping centres potentially offer great opportunities for the regeneration of urban areas. However, in order to determine what type of housing and what duration of use should be preferred in cities (both old and new buildings), a more rigorous calculation of housing needs is needed.