In 1966, readers of issue 164 of New worlds Magazine (1946 – 1997) was pleased to receive a review by author JG Ballard (15 November 1930 – 19 April 2009) The JeteeChris Marker’s time travel short film about time and memory, which was shown for the first time in London, and his essay “The Coming of the Unconscious”. In it, the British author writes about the surrealist paintings that influenced many of his early novels.

JG Ballard’s website states:

Although this appears to be a review of two books, this is actually an opportunity for JGB to comment on one of his favorite topics: “The ubiquity of surrealism is proof enough of its success. The landscapes of the soul, the juxtaposition of the bizarre and the familiar, and all the techniques of violent impact have become standard in advertising and cinema, not to mention science fiction.”

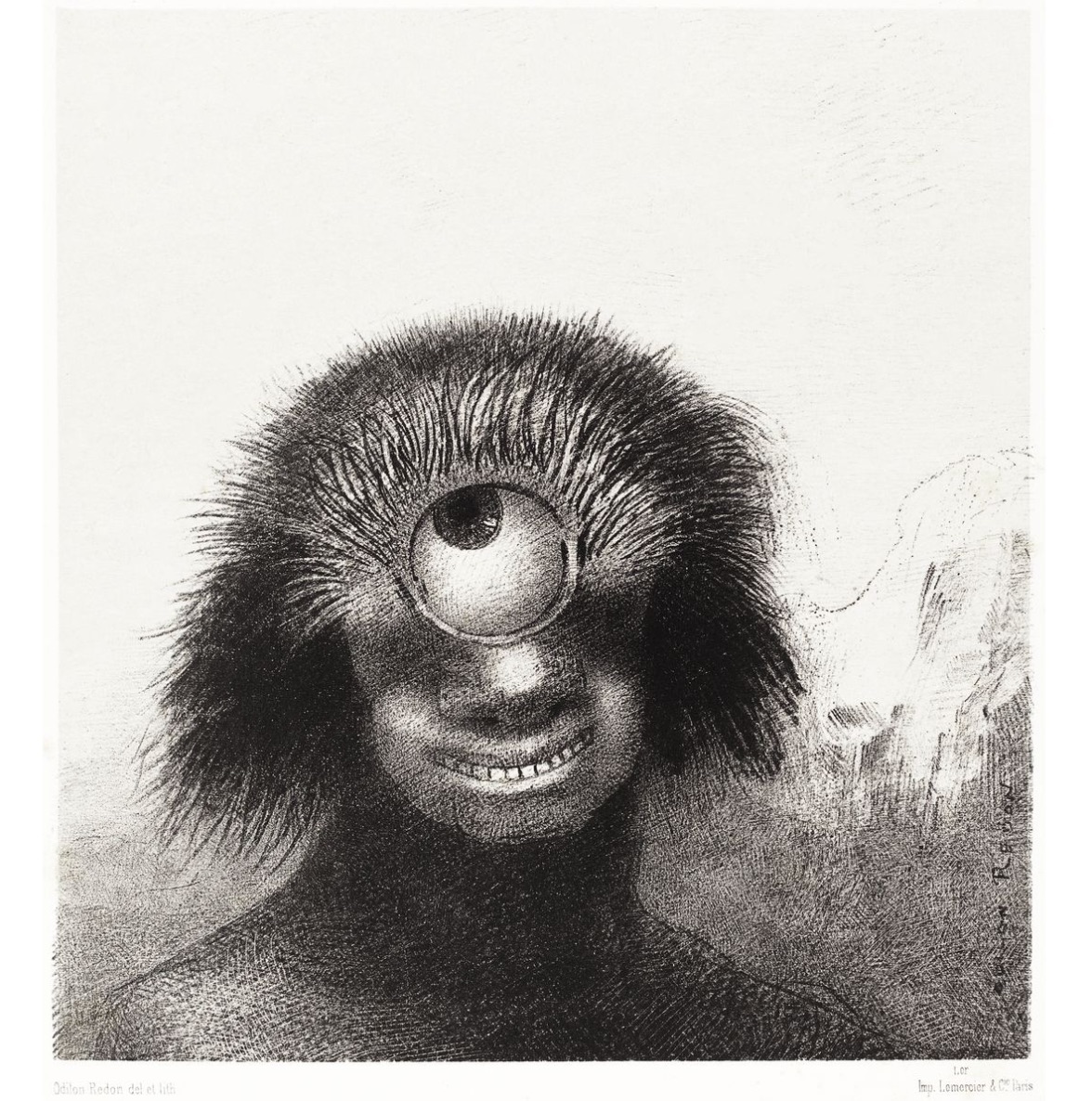

Ballard begins his reflection on the power and relevance of Surrealism with a quote from the French symbolist artist Odilon Redon (April 20, 1840 – July 6, 1916):

The images of Surrealism are the iconography of inner space. Surrealism is generally considered to be the lurid manifestation of a fantastic art that deals with dream and hallucination states. In fact, in the words of Odilon Redon, it is the first movement to put “the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible.”

What uniquely characterizes this fusion of the outer world of reality and the inner world of the psyche (which I have called “inner space”) is its redemptive and therapeutic power. Moving through these landscapes is a journey back to one’s innermost being.

Deformed polyp floating on the shores – Odilon Redon – buy this picture

John Coulthart adds that the list does not include all the surreal works of art that shaped Ballard’s thinking:

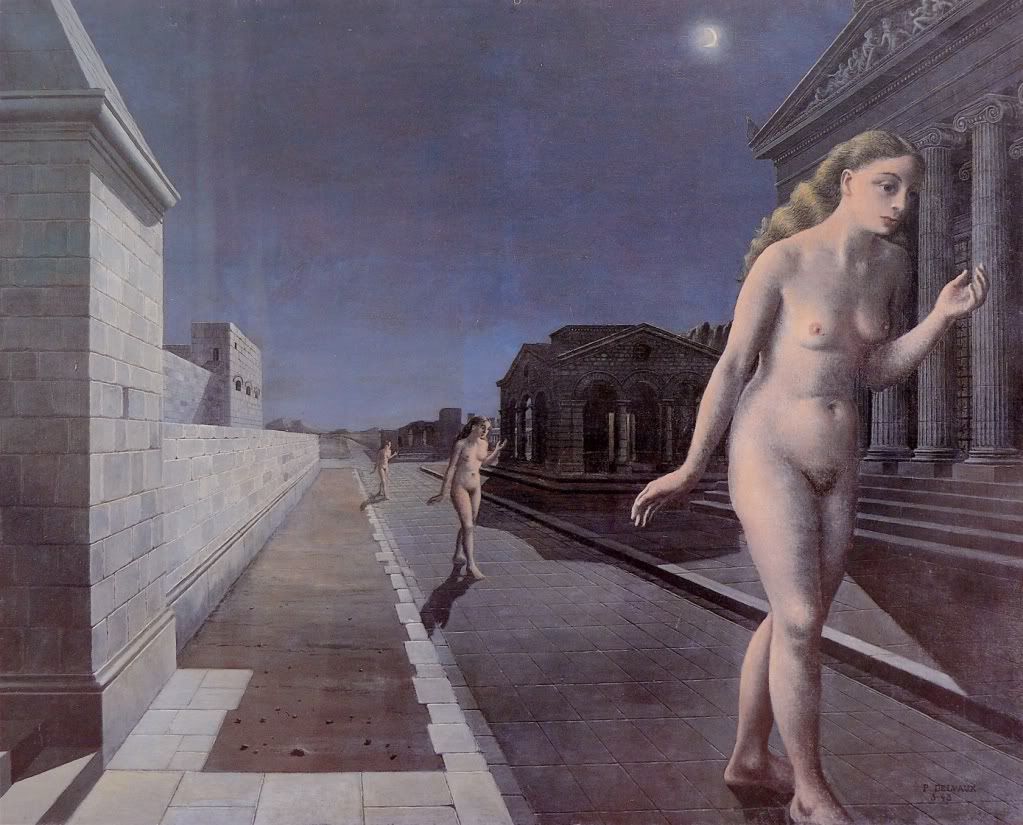

The following list comes towards the end of the text and should not be considered Ballard’s final selection. For example, Yves Tanguy is missing, although Tanguy’s art is in The drought. Nor Paul Delvaux, an artist whom Ballard liked so much that he commissioned Brigid Marlin to recreate the two Delvaux paintings destroyed in World War II. One Delvaux painting that still exists, The Echois mentioned in The day of eternitya story that Ballard probably wrote at this time and which was published in New worlds 170.

Giorgio de Chirico: The Disturbing Muses.

An indeterminate anxiety has begun to spread across the deserted square. The symmetry and regularity of the arcades conceals an intense inner violence; this is the face of a catatonic retreat. The space in this painting, like the intervals within the arcades, contains an oppressive negative time. The smooth, egg-shaped heads of the mannequins are devoid of features and sensory organs, but are marked with cryptic signs. These mannequins are people from whom every transitional time has been stripped away, they have been reduced to the essence of their own geometry.

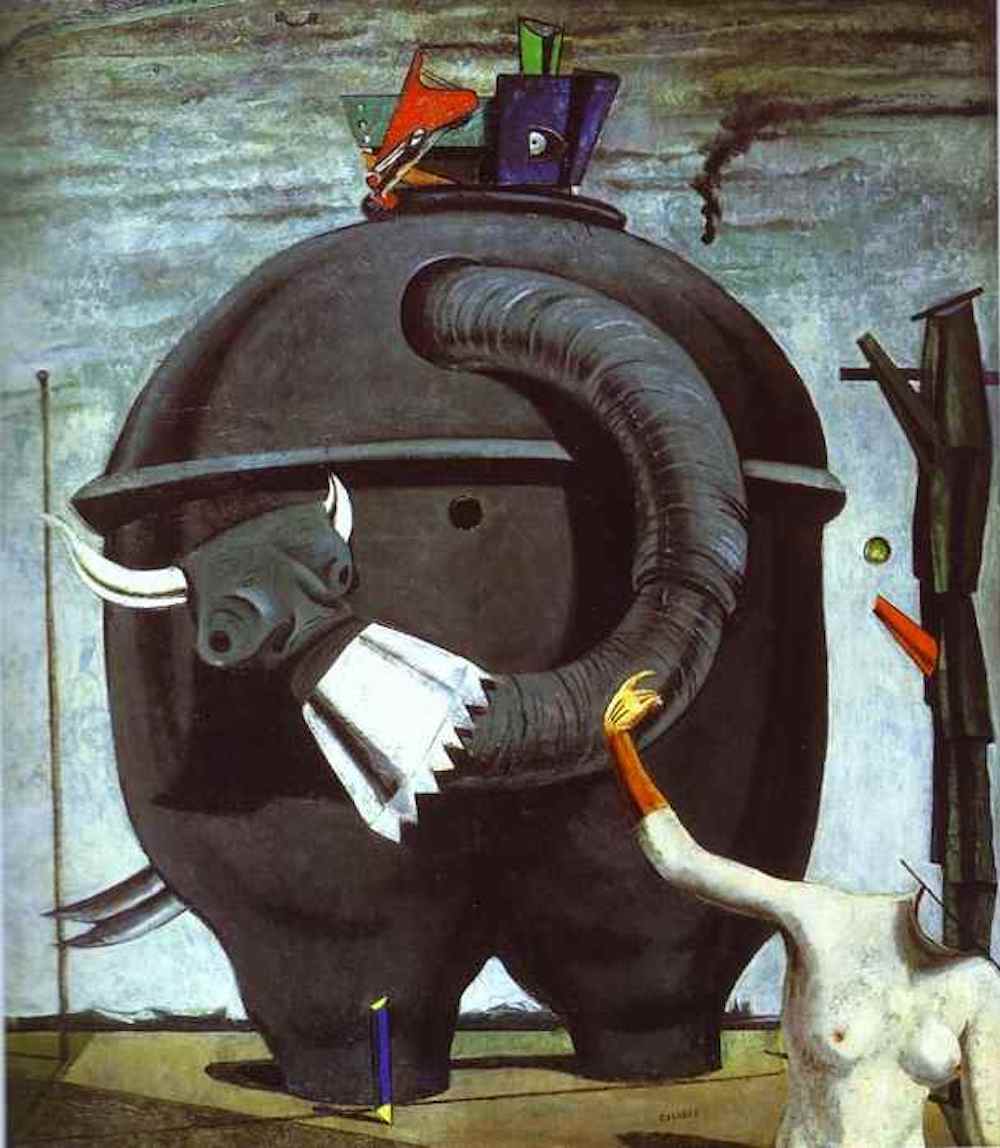

Max Ernst: The Elephant of Celebes.

A large cauldron with legs from which a pipe protrudes, ending in a bull’s head. A decapitated woman points to it, but the elephant looks up to the sky. Fishes float high in the clouds. Ernst’s wise machine, hot cauldron of time and myth, is the protective deity of the inner space, the benevolent Minotaur of the labyrinth.

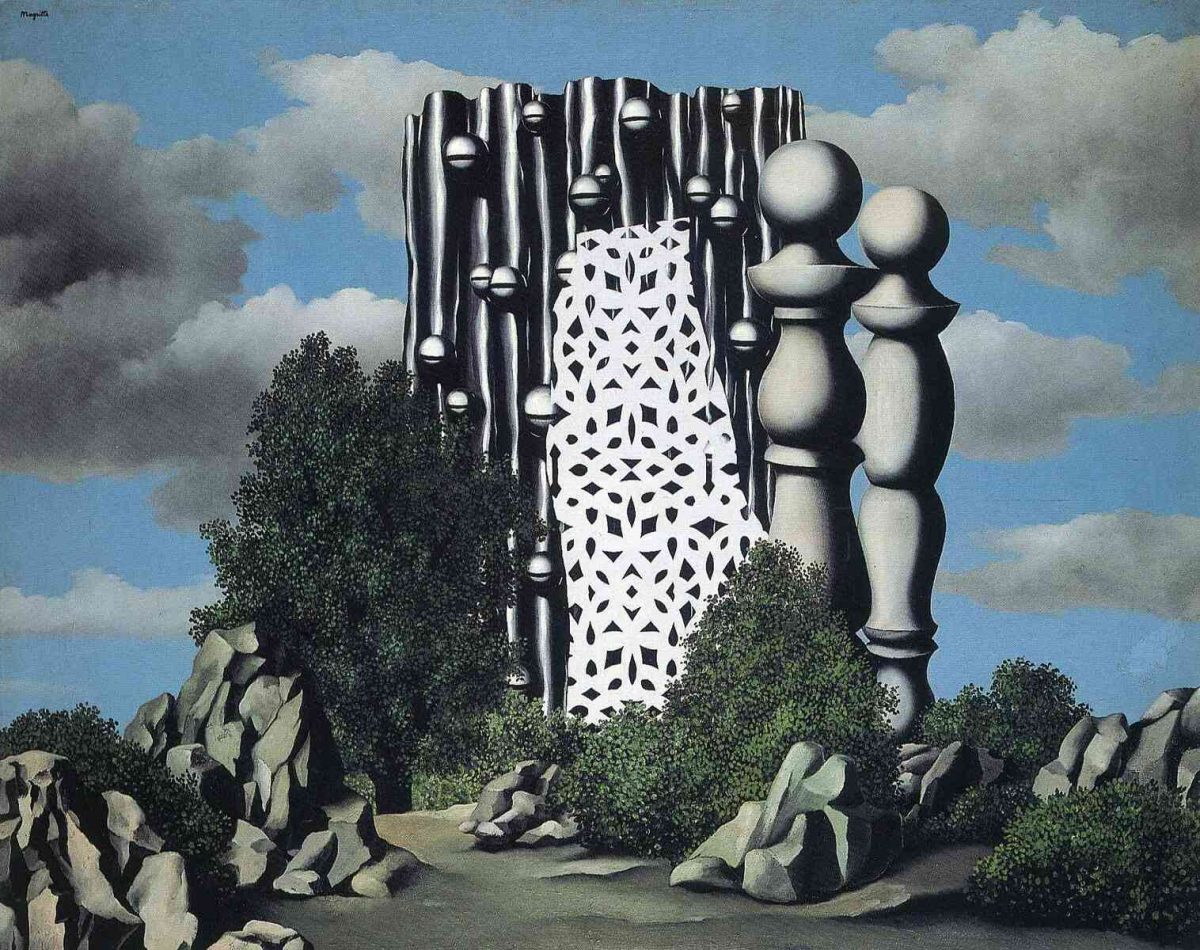

René Magritte: The Annunciation.

A stony path leads between dusty olive trees. Suddenly, a strange structure blocks our way. At first glance, it seems to be some kind of gazebo. A white lattice hangs like a curtain over the dark façade. Two elongated chess pieces stand on one side. Then we see that this is by no means a gazebo in which we can rest. This terrifying structure is a neuronic totem, its round and connected shapes are a fragment of our own nervous system, perhaps an insoluble code that contains the functioning of our journey through time and space. The announcement is that of a unique event, the first externalization of a neural interval.

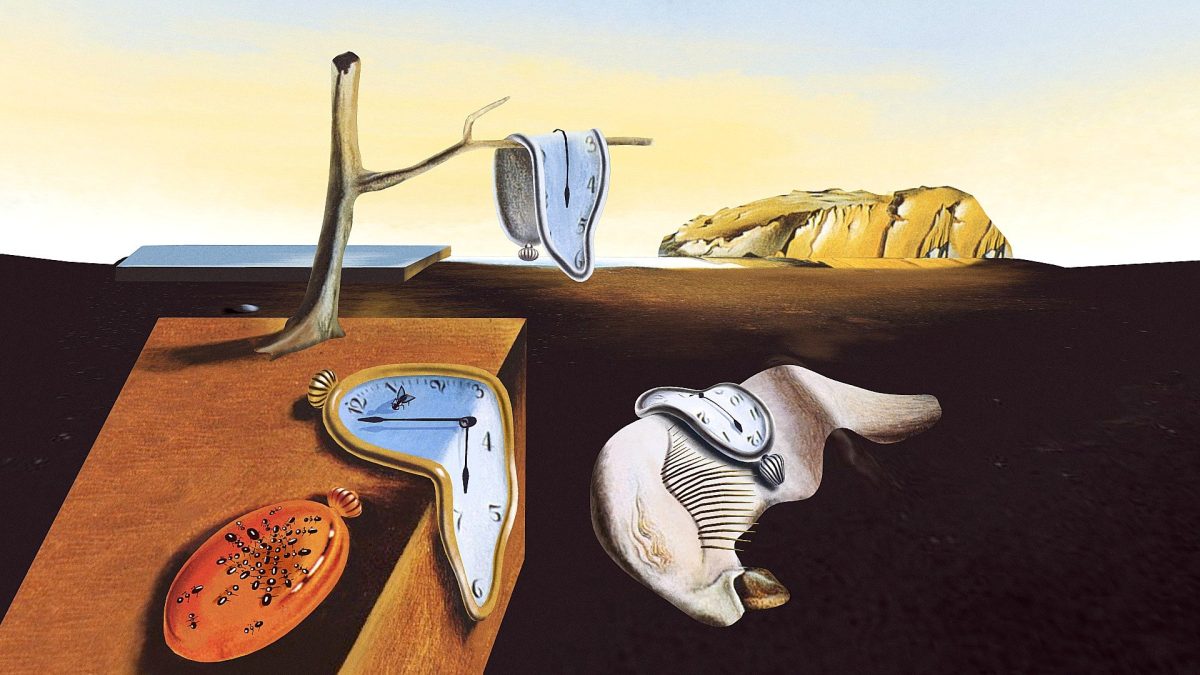

Salvador Dali: The Persistence of Memory.

The empty beach with its melted sand is a symbol of total psychic alienation, a definitive ossification of the soul. Time is no longer valid here, the clocks have begun to melt and drip. Even the embryo, symbol of secret growth and possibilities, is drained and limp. These are the remains of a remembered moment. The most notable elements are the two rectilinear objects, formalizations of sections of the beach and the sea. The displacement of these two images through time and their connection to our own four-dimensional continuum has distorted them into the rigid and unyielding structures of our own consciousness. Likewise, the rectilinear structures of our own conscious reality are distorted elements from a calm and harmonious future.

Oscar Dominguez: Decacomania.

By crushing gouache, Dominguez created striking landscapes of porous rock, drowned seas and coral. These coded terrains are models of the organic landscapes embedded in our central nervous system. Their closest counterparts in the external world of reality are those to which we respond most: igneous rock, dunes, drained deltas. Only these landscapes contain the psychological dimensions of nostalgia, memory and emotion.

Max Ernst: The Eye of Silence.

This swirling landscape, with its wild rocks rising into the air above the silent swamp, has acquired an organic life more real than that of the lonely nymph sitting in the foreground. These rocks have the luminosity of organs that have just been exposed to light. The real landscapes of our world are seen for what they are – the palaces of flesh and bone that are the living facades that enclose our own subliminal consciousness.

Ballard concludes with an observation about his age – he could be speaking of the present day:

The techniques of surrealism are particularly relevant at this moment, when the fictional elements in the world around us are multiplying to such an extent that it is almost impossible to distinguish between the “real” and the “false” – the terms no longer have any meaning. The faces of public figures are paraded before us as if from an endless global pantomime, they and the events in the world in general have the persuasiveness and reality of those depicted on giant billboards. The task of the arts seems more and more to be to isolate the few elements of reality from this melange of fictions, not some metaphorical “reality” but simply the basic elements of perception and attitude that are the pillars and supports of our consciousness.

Paul Delvaux, The Echo

Surrealism offers an ideal tool for exploring these ontological goals: the meaning of time and space (for example, the special significance of rectilinear forms in memory), of landscape and identity, the role of the senses and emotions in these contexts. As Dali noted, after Freud’s exploration of the psyche, it is now the external world that needs to be eroticized and quantified. The replication of past traumas and experiences, the discharge of anxieties and obsessions through landscape states, architectural portraits of individuals—these more serious aspects of Dali’s work illustrate some of the uses of surrealism. It offers a neutral zone or clearing house where the confused currencies of the inner and outer worlds can be standardized against each other.

At the same time, we should not forget the magical and surprising elements that await us in this realm. In the words of André Breton: “The confidence of madmen: I would risk my life to provoke them. They are people of scrupulous honesty, whose innocence is equal only to mine. Columbus had to sail with madmen to discover America.”

Mom, Dad is hurt!, Yves Tanguy

‘The Coming of the Unconscious’ was reprinted several times after its first publication: in a collection of stories, The overloaded man (1967) and in the essay and review collection A User’s Guide to the Millennium (1996).